Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Ambiguity in Life Detection

How likely are we to find a definitive biosignature once we begin analyzing the atmospheres of nearby rocky exoplanets? We have some ideal candidates, after all, with stars like TRAPPIST-1 yielding not one but three potentially life-bearing worlds. The first thing we’ll have to find out is whether any of these planets actually have atmospheres, and what their composition may be.

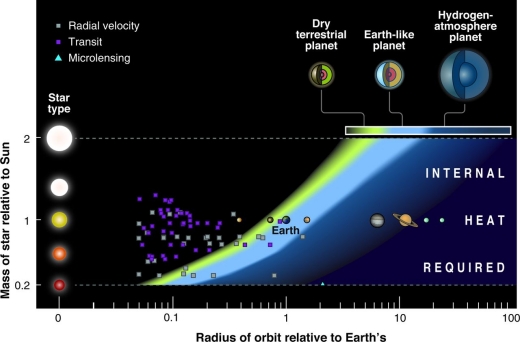

‘Habitable zone’ is a fluid concept, and that’s not just a reference to liquid water on the surface. A relatively dry terrestrial planet, one with little surface water and not a lot of water vapor in the atmosphere, might avoid a runaway greenhouse and manage to stay habitable in an orbit closer to a G-class star than Earth. A planet with an atmosphere dominated by hydrogen could maintain warm temperatures even at 10 AU and beyond. So we’ll need to find out what any exoplanet atmosphere is made of, and weigh that against its orbital position near its star.

Image: An extended habitable zone that captures some of the more modern thinking about habitable planets. The light blue region depicts the habitable zone for planets with N2-CO2-H2O atmospheres. The yellow region shows the habitable zone as extended inward for dry planets, with little surface water and little water vapor in the atmosphere, as dry as 1% relative humidity. The outer darker blue region shows the outer extension of the habitable zone for hydrogen-rich atmospheres and can extend even out to free-floating planets with no host star. The solar system planets are shown with images. Known exoplanets are shown with symbols [here, planets with a mass or minimum mass less than 10 Earth masses or a radius less than 2.5 Earth radii]. Credit: Image and caption by Sara Seager.

When we use terms like ‘Earth-like’ in relation to atmospheres, we’re talking about nitrogen, oxygen and carbon dioxide, but we also have to remember that atmospheres develop and change over time. The early Earth would have begun with abundant hydrogen and helium, but volcanic eruptions could later supply carbon dioxide, water vapor, sulphur and more. We needed a huge oxygenation event two and a half billion years ago to bring oxygen levels up. Exactly where would an exoplanet be in its development during the time we are able to observe it?

So assume we start examining those interesting transiting worlds around TRAPPIST-1 and find that one of them shows traces of oxygen. Cause for celebration? Certainly, but we’re still a long way from determining whether life is present. Because there are models for oxygen-rich atmospheres that are completely abiotic. TRAPPIST-1 is an M-dwarf, and we know that ultraviolet light from the star can break down carbon dioxide, adding oxygen to the mix.

Water vapor in a planetary atmosphere can likewise be broken down into hydrogen and oxygen through UV radiation, so oxygen by itself is not enough. We saw yesterday that a simultaneous detection of methane would be a much more satisfactory signature. Here we’re looking at two gases that should remove each other from the atmosphere in short order unless there were something there to sustain them. Let me quote Stephen Reinhard (NASA GSFC, and a project scientist on the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite mission) on the matter:

“There are a couple of things we like to see as a potential for habitability — one of them is water, which is probably the single most important, because as far as we know, all life that we’re familiar with depends on water in some way. The other is methane, which on our Earth is produced almost entirely biologically. When you start seeing certain combinations of all of these things appearing together — water, methane, ozone, oxygen — it gives you a hint that the chemistry is out of equilibrium. Naturally, planets tend to be chemically stable. The presence of life throws off this balance.”

Now that sounds pretty straightforward, and surely a simultaneous detection of oxygen and methane would make a strong case for life. But even here, we have to be careful. If there are abiotic sources of oxygen, there are also abiotic sources of methane, even if most of the methane found in our own planet’s atmosphere is associated with living processes. Volcanism is one methane source, and we’ve learned recently that carbon-rich micrometeoroids can produce methane as they burn up upon entry into a planet’s atmosphere.

Systems with larger amounts of dust than our own could conceivably produce a high enough methane signature in a planetary atmosphere to be noted by our space observatories, further complicating the search for life. Here again we’ll have to pay particular attention to the age of the system we’re studying, for systems with dense debris disks are those likely to produce this effect, with planets perhaps undergoing their own version of our Late Heavy Bombardment, when some 3.9 billion years ago our world was pummeled by millions of collisions.

When I said yesterday that it was possible we might get a biosignature detection within as little as ten years, what I was really saying was that we might get some evidence of biology, but very likely it would be ambiguous and hotly contested. Rather than a sudden announcement that life has been found in another star system, the news is likely to emerge as a battle of competing analyses, trying to determine whether what we see could be explained without implicating life.

We also need to pay attention, as Sara Seager and colleagues are doing, to what other gases might be involved in biosignatures. Indeed, life on our planet produces thousands of different gases, most of them in small quantities that accumulate little in the atmosphere. Most are produced for reasons specific to the organism they support, and they do so guided by little more than evolutionary selection. The point here is that life on another world may have surface and atmospheric conditions that produce chemistries profoundly different from Earth’s.

Hence Seager’s interest in studying all the molecules that exist in gas form in a planetary atmosphere in conditions similar to the temperature and pressure of Earth. A recent paper on this work presents results from an examination of 14,000 molecules, about 2500 of which are hydrocarbons, with the goal of eventually producing a truly comprehensive list of biosignature gases and the false positives that accompany them. If there is one thing we can probably state with some confidence, it is that early exoplanet atmospheric studies will produce surprises.

Getting ready for them is what studies like Seager’s are all about. What we’re going to need as we begin to detect ambiguous evidence for biosignatures is a large space telescope well beyond WFIRST in capabilities, one capable of pulling in atmospheric data from enough exoplanets that we can begin to develop a statistical understanding of what we’re seeing. Designs like LUVOIR (Large UV/Optical/Infrared Surveyor) and HabEx (Habitable Exoplanet Imaging Mission) are under study, even as we look beyond them to the kind of mirror technologies that may allow still bigger instruments and more comprehensive analysis.

The Seager paper is Seager, Bains and Petkowski, “Toward a List of Molecules as Potential Biosignature Gases for the Search for Life on Exoplanets and Applications to Terrestrial Biochemistry,” Astrobiology 16(6) (June 201), 465-485 (abstract).

To See a Habitable World

Video presentations from the recent Tennessee Valley Interstellar Workshop are beginning to appear online. It’s welcome news for those of us who believe all conferences should be available this way, and a chance for Centauri Dreams readers to home in on particular presentations of interest. I published my Closing Remarks at TVIW right after the meeting and will watch with interest as the complete 2017 videos now become available. There are a number of these I’d like to see again.

All of this gets me by round-about way to Project Blue, the ongoing attempt to construct a small space telescope capable of directly imaging an Earth-like planet around Centauri A or B, if one is indeed there. For the other talk I gave at TVIW 2017 (not yet online) had to do with biosignatures, and the question of whether we had the capability of detecting one in the near future with the kind of missions now approved and being prepared for launch. This was delivered as part of a presentation and panel discussion with Greg Benford and Angelle Tanner (Mississippi State), one of the conference’s ‘Sagan Meetings.’

The answer is yes, though a highly qualified yes, and Project Blue could be a part of that. When we talk about biosignatures, we are presuming the ability to analyze a planet’s atmosphere, and that is something we’re fully capable of doing today. The fact that such analyses have involved hot gas giants should not deter us, for we’re shaping the methods that will eventually get us down to Earth-mass worlds. These planets won’t necessarily be Earth-like, for the first ones we’ll see in this range will be orbiting red dwarf stars in the immediate neighborhood.

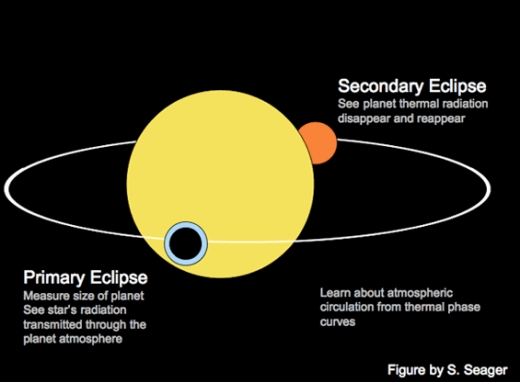

Image: Transmission spectroscopy illustrated. If we can find a transiting world, we can study both the primary eclipse as it moves across the face of the star and the secondary eclipse as the planet’s thermal radiation disappears behind it. Credit: Sara Seager (MIT).

There are reasons for that, most specifically the deep transit depth that an Earth-size planet would present when passing, in a habitable zone orbit, across the face of a nearby red dwarf. In the primary eclipse, some of the starlight we detect has passed through the planet’s atmosphere, giving us the chance to study its components. A biosignature gas is one that is produced by life and accumulates at detectable levels within an atmosphere. We’re especially interested in gases that are out of equilibrium, such as oxygen in the presence of methane.

The point here is that oxygen is unstable over geological timeframes, and would be depleted through reactions with volcanic gases and oxidation unless there existed a source to replace it. A combination of oxygen and methane would indicate a steady source of both, as James Lovelock noted in 1975. The combination is simply out of balance from what would occur through natural processes. Detecting it would indicate the probable presence of life on the planet.

False positive issues abound here, but let’s get into them tomorrow. Because I want to circle back to Project Blue at this point, to discuss the fact that beyond transmission spectroscopy, we have the capability of looking at planets through direct imaging. Coronagraphs are one way of suppressing the light of a central star, and so are starshades, the latter a possibility for the WFIRST mission, which could be constructed so as to be ‘starshade ready’ and thus capable of being joined in space by a later starshade mission that would fly tens of thousands of kilometers away and offer the prospect of detecting planets within 1 AU even of G-class stars like the Sun. In any case, WFIRST is being adapted for a coronagraph whether or not the starshade flies.

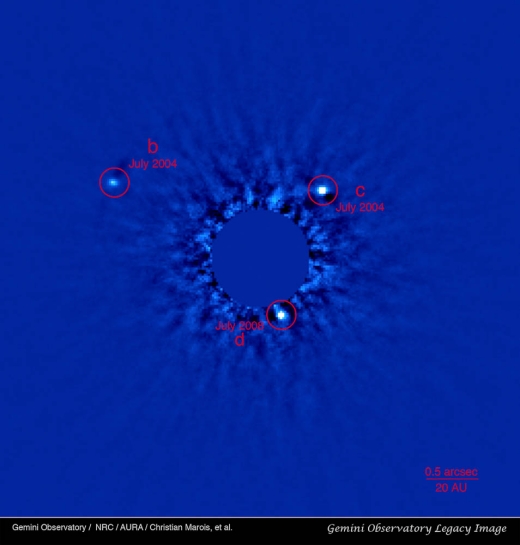

Image: Direct imaging at work. HR 8799 is a star a bit more massive than the Sun, and far younger, about 60 million years old. We see not one but three planets orbiting it. This is the first portrait of an exosolar system. It was announced at the same time as the Fomalhaut candidate, too, giving this system a tie as the first ever seen orbiting a Sun-like star. The planets, labeled b, c, and d, are about 7, 10, and 10 times the mass of Jupiter, respectively, and orbit their star at 68, 38, and 24 times the distance of the Earth from the Sun. It’s possible planets c and d are massive enough to qualify as brown dwarfs. Credit: Gemini Observatory.

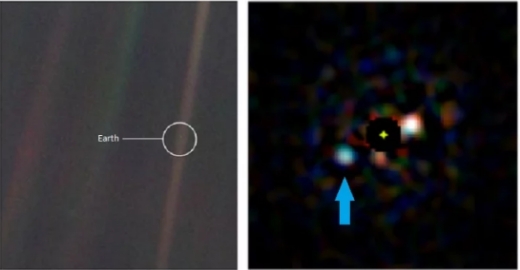

I provided the background for Project Blue at the end of September, describing the small telescope originally called ACEsat that, in the hands of Eduardo Bendek and Ruslan Belikov (NASA Ames) later morphed into the crowd-funded Project Blue design. The designers believe that this telescope would be fully capable of photographing a ‘pale blue dot’ around one or both of the primary Alpha Centauri stars, and that would mean we could dispense with transmission spectroscopy and deal with light directly from the planet in question to study its atmosphere.

The Project Blue campaign has a week to run in its attempt to reach a $175,000 goal (it’s 73 percent of the way there as of this morning). Giving the campaign an additional boost is the action of a donor who has pledged to match contributions until the goal is reached, making every dollar people contribute turn into two. Check the project’s Indiegogo page for further information about its light suppression techniques, which include not only a coronagraph but a deformable mirror, low-order wavefront sensors and software control algorithms to manipulate incoming light, as well as post processing methods that substantially enhance image contrast.

Image: (L) Voyager’s ‘pale blue dot’ photo of Earth from the edge of our Solar System; (R) A simulated image of a photo Project Blue aims to take of exoplanets around one of the stars in the Alpha Centauri system. (Credit: NASA JPL / Jared Males).

Have a look at the Project Blue page and help if you can. The goals involved are to set the science requirements for the mission, complete the opto-mechanical design and request industry letters of interest, while developing a mission performance simulator to analyze different configurations (the latter will eventually become available online).

A mission like Project Blue could conceivably move the timetable forward in terms of biosignature detection, if absolutely everything falls into place and the right kind of planet is indeed orbiting Centauri A or B. Thus, between upcoming red dwarf investigations using the James Webb Space Telescope (aided by data from the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite), and possible direct imaging of an Earth-like planet around the nearest star system, we could conceivably detect biosignatures within the next ten to fifteen years. It’s a stretch, and I’ll explain why tomorrow, but add a decade or two to the timeline and the odds begin to climb.

An Interstellar Visitor?

An object called A/2017 U1, whether it is an asteroid or a comet, is drawing attention because it seems to be an interstellar wanderer. Discovered on October 19 by the University of Hawaii’s Pan-STARRS 1 telescope on Haleakala, the object was quickly submitted to the Minor Planet Center by Rob Weryk (University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy, IFA). Weryk was subsequently able to identify the object in Pan-STARRS imagery from the previous night.

Image: This animation shows the path of A/2017 U1, which is an asteroid — or perhaps a comet — as it passed through our inner solar system in September and October 2017. From analysis of its motion, scientists calculate that it probably originated from outside our Solar System. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

Thus a nightly search for near-Earth objects may have uncovered an object whose origins lie much further away. A/2017 U1 is about 400 meters in diameter and on a highly unusual trajectory, one that fits neither an asteroid or comet from our own Solar System. Davide Farnocchia (JPL) is a scientist at NASA’s Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS):

“This is the most extreme orbit I have ever seen,” said Farnocchia. “It is going extremely fast and on such a trajectory that we can say with confidence that this object is on its way out of the Solar System and not coming back.”

Thus we seem to be looking at an object unattached to any star. That such objects exist is hardly a surprise, as we already know there is a robust population of planets that have been ejected from their own stellar systems and wander alone through interstellar space. But if confirmed as such a wandering object, A/2017 U1 would be the first ever observed coming through our own Solar System.

“We have long suspected that these objects should exist, because during the process of planet formation a lot of material should be ejected from planetary systems. What’s most surprising is that we’ve never seen interstellar objects pass through before,” said Karen Meech, an astronomer at the IfA specializing in small bodies and their connection to Solar System formation.

Coming from the direction of the constellation Lyra and moving at 25.5 kilometers per second, A/2017 U1 evidently entered our Solar System from above the ecliptic, crossing the ecliptic plane inside the orbit of Mercury and reaching perihelion on September 9. As the illustration above makes clear, its trajectory was deflected by the Sun’s gravity and it passed ‘under’ the Earth’s orbit on October 14 at a distance of some 24 million kilometers. It is now back above the plane of the planets, moving at 44 kilometers per second, heading toward Pegasus.

Image: The Pan-STARRS1 Observatory on Halealakala, Maui, opens at sunset to begin a night of mapping the sky. Credit: Photo by Rob Ratkowski.

We’ll have to see what naming conventions come into play if this object is indeed confirmed as an interstellar traveler, putting the onus on the International Astronomical Union to come up with something interesting. You may remember that asteroid 31/439 wound up getting named ‘Rama’ in Arthur C. Clarke’s fine tale Rendezvous with Rama (1973), though we’re unlikely to find that A/2017 U1 is as intriguing as Clarke’s mysterious starship bound for the Magellanics.

Meanwhile, we’re reminded of yet another reason why wide-field surveys of the sky make sense. While we engage in the great task of planetary protection, we also make discoveries like this one, following up with the kind of detailed observations now underway. Compiling the necessary data will help us pin down the origin of this intriguing visitor.

Planet Formation in Cometary Rings

Just how do you go about building a ‘super-Earth’? One possibility may be emerging in the study of young debris disk systems with thin, bright outer rings made up of comet-like bodies. Three examples are under scrutiny in work discussed at the recent American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting in Provo, Utah. Here, Carey Lisse (JHU/APL) described his team’s results in studying the stars Fomalhaut, HD 32297 and HR 4796A.

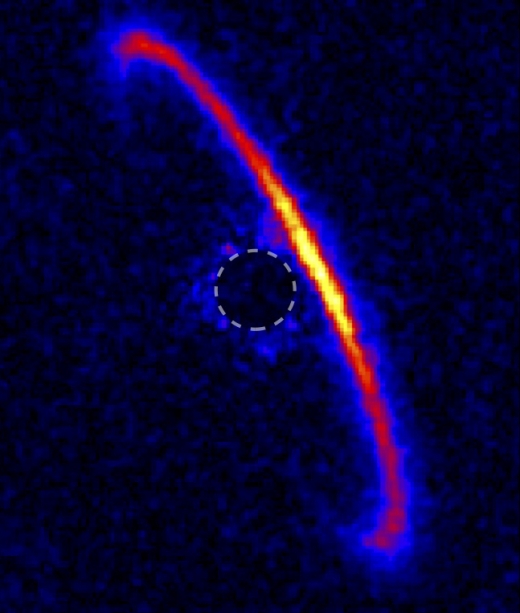

What the scientists are finding is that dense rings of comets can become a construction zone for planets of super-Earth size. The makeup of the material in these ring systems varies, from two that are rich in ice (Fomalhaut and HD 32297) to one that is depleted in ice but rich in carbon (HR 4796A). Take a look at the image below, showing the ring surrounding HR 4796A, and you’ll see how strikingly tight the band of dust around this relatively young stellar system is.

Image: Gemini Planet Imager observations reveal a complex pattern of variations in brightness and polarization around the HR 4796A disk. Credit: Marshall Perrin (Space Telescope Science Institute), Gaspard Duchene (UC Berkeley), Max Millar-Blanchaer (University of Toronto), and the GPI Team.

What causes the dust ring here? Lisse believes its red color is the result of the burnt-out rocky remains of comets, with the ring system close enough to the central star that the original materials have largely boiled off. At Fomalhaut and HD 32297, cometary dust containing ices is found, the ring systems being far enough from the central star that their comets remain cold and stable.

But the tight structure of these three ring systems is still problematic, because in young systems we would expect to see a much less orderly situation as the early era of planet formation proceeds. We also see little circumstellar gas in these systems.

Here we might think of what Cassini showed us at Saturn in the form of small ‘shepherding’ moons that preserve ring structure. Could something similar be happening around these stars, varying according to temperature, as emerging planets begin to take shape? Lisse believes this to be the case:

“Comets crashing down onto these growing planet surfaces would kick up huge clouds of fast-moving, ejected ‘construction dust,’ which would spread over the system in huge clouds. The only apparent solution to these issues is that multiple mini-planets are coalescing in these rings, and these small bodies, with low kick-up velocities, are shepherding the rings into narrow structures — much in the same way many of the narrow rings of Saturn are focused and sharpened.”

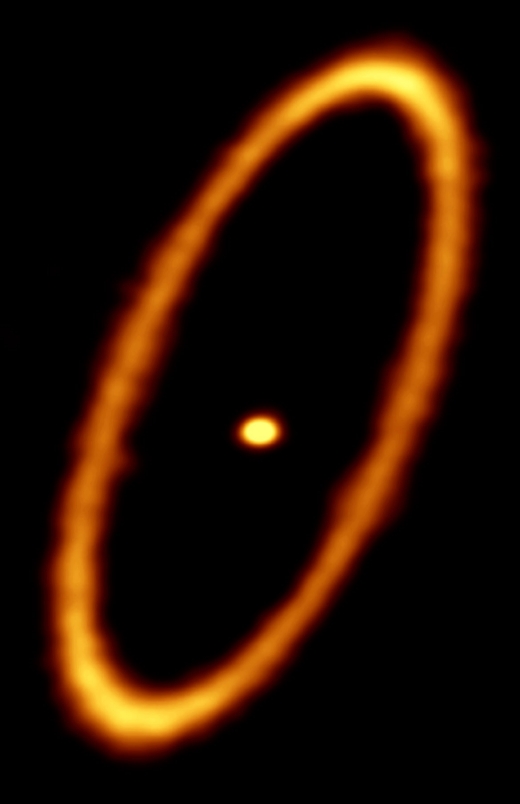

Image: ALMA image of the debris disk in the Fomalhaut star system. The ring is approximately 20 billion kilometers from the central star and about 2 billion kilometers wide. The central dot is the unresolved emission from the star, which is about twice the mass of our Sun. Credit: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); M. MacGregor.

This is an interesting model because it distributes planet formation into a series of small processes within the ring structure. Lisse and team believe that in Fomalhaut and HD 32297, they are seeing the formation of planets out of materials supplied by millions of comets, with planetary cores emerging similar to those of the ice giants Uranus and Neptune. But in this case, the gas disks that would contribute to atmospheres are gone. In HR 4796A, with a warmer dust ring, the core building materials are reduced to leftover carbon and rocky debris.

From a recent Lisse et al. paper on this star:

Our results are consistent with an HR 4796A system consisting of a narrow sheparded belt of devolatilized cometary material associated with multiple rocky subcores forming a planet, and a small steady stream of dust inflowing from this belt to a rock sublimation zone at ~1 AU from the primary. These subcores were built from comets that have been actively emitting large, reddish dust for > 0.4 Myr at ~100K (the temperature at which cometary activity onset is seen in our Solar System).

The potential result: The kind of ‘super-Earth’ planets we do not see in our own Solar System (unless we find such in the conjectured ‘Planet Nine’). The Kepler results showed us super-Earths in abundance. Now this cometary ring theory gives us a way to account for their formation. Still to be resolved: The amount of time it is taking for these planets to finish their formation, a period that has been long enough to see the primordial gas in the stellar disks stripped away. Even Lisse concludes that the issue remains ‘a big mystery.’

The paper on HR 4796A is Lisse et al., “Infrared Spectroscopy of HR 4796A’s Bright Outer Cometary Ring + Tenuous Inner Hot Dust Cloud,” accepted at the Astronomical Journal (preprint).

Probing General Relativity with Neutron Stars

Another of those ‘new eras’ I talked about in yesterday’s post is involved in the latest news on gravitational waves. Let’s not forget that it was 50 years ago — on November 28, 1967 — that Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Antony Hewish observed the first pulsar, now known to be a neutron star. It made the news at the time because the pulses, separated by 1.33 seconds, raised a SETI possibility, leading to the playful designation LGM-1 (‘little green men’) for the discovery.

We’ve learned a lot about pulsars emitting beams at various wavelengths since then and the SETI connection is gone, but before I leave the past, it’s also worth recognizing that our old friend Fritz Zwicky, working with Walter Baade, first proposed the existence of neutron stars in 1934. The scientists believed that a dense star made of neutrons could result from a supernova explosion, and here we might think of the Crab pulsar at the center of the Crab Nebula, an object whose description fits the pioneering work of Zwicky and Baade, and also tracks the work of Franco Pacini, who posited that a rotating neutron star in a magnetic field would emit radiation. Likewise a pioneer, Pacini suggested this before pulsars had been discovered.

Writing about all this takes me back to reading Larry Niven’s story ‘Neutron Star,’ available in the collection by the same name, when it first ran in a 1966 issue of IF. Those were interesting days for IF, but I better cut that further digression off at the source — more about the magazine in a future post. ‘Neutron Star’ is the story where Beowulf Shaeffer, a familiar character in Larry’s Known Space stories, first appears. If you want to see a neutron star up close and learn what its tidal forces can do, you can’t beat Niven’s tale.

Typically, a neutron star will get up to two solar masses while showing a diameter of a mere 20 kilometers, telling us it’s made of a kind of dense matter about which we have much to learn. Scientists at the Max Planck Institutes for Gravitational Physics and for Radio Astronomy have been looking at two major tools for studying the intense gravity associated with neutron stars: Pulsar timing and gravitational wave observations like the recent GW170817 event.

What’s interesting here is that neutron stars can help us investigate theories of gravity in which the gravitational fields associated with their interactions may differ from what General Relativity predicts. Lijing Shao, lead author of the paper coming out of this work, notes that alternate theories of gravity will produce different predictions on the behavior of binary neutron star systems. The paper gives us a glimpse of the kind of analyses gravitational wave astronomy will enable.

“The gravitational acceleration at a neutron star’s surface is about 2×1011 times that of the Earth which makes them excellent objects to study Einstein’s general relativity and alternative theories in the strong-field regime. In a systematic investigation with pulsar timing technologies, we were able to put constraints on a class of alternative gravity theories showing for the first time in detail how they depend on the physics of the extremely dense matter they contain.”

All this emerges as the “equation of state” of neutron stars. Equations of state relate pressure, volume and temperature in a particular substance that is in thermodynamic equilibrium. Shao and colleagues have been studying possible equations of state for five binary pulsar systems, each of which contains a neutron star and a white dwarf. They believe that gravitational wave detectors will soon become sensitive enough to investigate alternate gravitational theories.

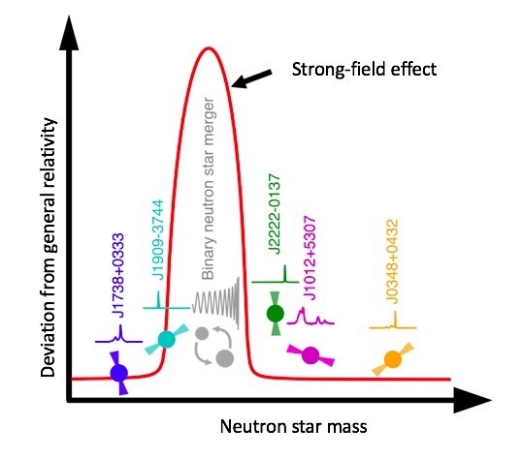

Image: The constraints on deviations from general relativity set by pulsar timing leave a gap between about 1.6 – 1.7 solar masses. Gravitational wave observations of binary neutron stars of the appropriate mass could fill this gap and thus further constrain alternative theories of gravity. Credit and Copyright: L. Shao (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics & Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy), N. Sennett, A. Buonanno (Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics).

Co-author Alessandra Buonanno, who is also director of the Astrophysical and Cosmological Relativity division at the Institute in Potsdam, puts the matter this way:

“The LIGO-Virgo detectors may soon discover binary neutron star systems with suitable masses that could improve the constraints set by binary-pulsar tests for certain equations of state and thus put Einstein’s general relativity and alternative theories to a qualitatively new test.”

Thus we’re pushing into the early days of gravitational wave astronomy by looking at conditions in ultra-strong gravitational fields, with an eye toward yet another way of probing General Relativity. Improving the analyses already made through pulsar timing alone, gravitational waves will help us probe deeper, especially as we begin to get better mass measurements for known pulsars, where in many cases the uncertainties are large. As the paper notes:

Our comparisons between binary pulsars and GWs made use of the current limits of the former and the expected limits of the latter. It shows that advanced and next-generation ground-based GW detectors have potential to further improve the current limits set by pulsar timing.

The paper is Shao et al., “Constraining nonperturbative strong-field effects in scalar-tensor gravity by combining pulsar timing and laser-interferometer gravitational-wave detectors,” accepted at Physical Review X (preprint).

A Deep Data Dive for Gravitational Lenses

We seem to be entering ‘new eras’ faster than I can track. Certainly the gravitational wave event GW170817 demonstrates how exciting the prospects for this new kind of astronomy are, with its discovery of a neutron star merger producing a heavy-metal seeding ‘kilonova.’ But remember, too, how early we are in the exoplanet hunt. The first exoplanets ever detected were found as recently as 1992 around the pulsar PSR B1257+12. Discoveries mushroom. We’ve gone from a few odd planets around a single pulsar to thousands of exoplanets in a mere 25 years.

We’re seeing changes that propel discovery at an extraordinarily fast pace. Look throughout the spectrum of ideas and you can also see that we’re applying artificial intelligence to huge datasets, mining not only recent but decades-old information for new insights. Today’s problem isn’t so much data acquisition as it is data storage, retrieval and analysis. For the data are there in vast numbers, soon to be augmented by huge new telescopes and space missions that will take our analysis of planetary atmospheres down from gas giants to Earth-size worlds.

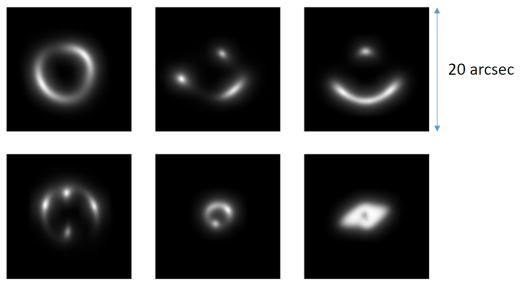

Consider what a team of European astronomers has come up with by way of gravitational lensing. Working at universities in Groningen, Naples and Bonn, the scientists have deployed artificial intelligence algorithms similar to those that have been used in the marketplace by the likes of Google, Facebook and Tesla. Feeding a neural network with astronomical data, the team was able to spot 56 new gravitational lens candidates. All of this in a field of study that normally demands sorting thousands of images and putting human volunteers to work.

Image: With the help of artificial intelligence, astronomers discovered 56 new gravity lens candidates. This picture shows a sample of the handmade photos of gravitational lenses that the astronomers used to train their neural network. Credit and copyright: Enrico Petrillo (Rijksuniversiteit Groningen).

The team’s astronomical data were drawn from the optical Kilo Degree Survey (KiDS). Working the data is a ‘convolutional neural network’ of the kind Google’s AlphaGo used to beat Lee Sedol, the world’s best Go player. Carlo Enrico Petrillo (University of Groningen, The Netherlands) and team first fed the network millions of training images of gravitational lenses, a project that displayed the lensing properties the researchers wanted to identify.

The images from the Kilo Degree Survey cover about half of one percent of the sky. Matching the new imagery with its training images, the neural network found 761 lens candidates, which subsequent analysis by the astronomers whittled down to 56. These are all considered lensing candidates in need of confirmation by telescopes. The network rediscovered two known lenses but missed a third known lens considered too small for its training sample.

For Carlo Enrico Petrillo, the implications are clear:

“This is the first time a convolutional neural network has been used to find peculiar objects in an astronomical survey. I think it will become the norm since future astronomical surveys will produce an enormous quantity of data which will be necessary to inspect. We don’t have enough astronomers to cope with this.”

Exactly so. We’re accumulating data faster than we can analyze our material, which is why artificial intelligence advances are so telling. Training the network to recognize smaller lenses and to reject false ones is next on the team’s agenda. In the context of improving AI, bear in mind the recent major upgrade of Google’s AlphaGo to AlphaGo Zero, which defeated regular AlphaGo 100 games to 0. The new version trained itself from scratch in three days.

Image: With the help of artificial intelligence, astronomers discovered 56 new gravity lens candidates. In this picture are three of those candidates. Credit and Copyright: Carlo Enrico Petrillo (University of Groningen).

The paper is Petrillo et al., “Finding strong gravitational lenses in the Kilo Degree Survey with Convolutional Neural Networks,” Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society Vol. 472, Issue 1 (21 November 2017), pp. 1129-1150 (abstract). On AlphaGo Zero, see Silver et al., “Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge,” Nature 550 (19 October 2017), pp. 354-359 (abstract).