Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

A $100 Million Infusion for SETI Research

SETI received a much needed boost this morning as Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner, along with physicist Stephen Hawking and a panel including Frank Drake, Ann Druyan, Martin Rees and Geoff Marcy announced a $100 million pair of initiatives to reinvigorate the search. The first of these, Breakthrough Listen, dramatically upgrades existing search methods, while Breakthrough Message will fund an international competition to create the kind of messages we might one day send to other stars, although the intention is also to provoke the necessary discussion and debate to decide the question of whether such messages should be sent in the first place.

With $100 million to work with, SETI suddenly finds itself newly affluent, with significant access to two of the world’s largest telescopes — the 100-meter Green Bank instrument in West Virginia and the 64-meter Parkes Telescope in New South Wales. The funding will also allow the Automated Planet Finder at Lick Observatory to search at optical wavelengths. Milner’s Breakthrough Prize Foundation is behind the effort through its Breakthrough Initiatives division, a further indication of the high-tech investor’s passion for science.

Image: Internet investor Yuri Milner announcing the Breakthrough Listen and Breakthrough Message initiatives in London at The Royal Society. Credit: Breakthrough Prize Foundation.

Organizers explained that the search will be fifty times more sensitive than previous programs dedicated to SETI, and will cover ten times more of the sky than earlier efforts, scanning five times more of the radio spectrum 100 times faster than ever before. Covering a span of ten years, the plan is to survey the one million stars closest to the Earth, as well as to scan the center of the Milky Way and the entire galactic plane. Beyond the Milky Way, Breakthrough Listen will look for messages from the nearest 100 galaxies.

According to the news release from Breakthrough Initiatives, if a civilization based around one of the thousand nearest stars transmits to us with the power of the aircraft radar we use today, we should be able to detect it. A civilization transmitting from the center of the Milky Way with anything more than twelve times the output of today’s interplanetary radars should also be detectable. At optical wavelengths, a laser signal from a nearby star even at the 100-watt level is likewise detectable.

Frank Drake noted the changes in technology that have made such searches possible:

“Today we have major developments in digital technology and also the necessary telescopes to monitor billions of channels at the same time. But we needed the funding to allow all this to proceed. Fortunately there are private benefactors who realize the significance of the search. We will finally have stable funding so we can plan from one year to the next. This will be the most enduring search ever launched, a great milestone and our best chance for success.”

Image: Martin Rees, Frank Drake, Ann Druyan and Geoff Marcy at the announcement. Credit: Breakthrough Prize Foundation.

Geoff Marcy (UC-Berkeley) pointed out that we simply have no idea whether the nearest civilization is ten light years or 10 million light years away, but the Breakthrough Listen project will attempt to find out by scanning 10 billion frequencies simultaneously.

“We will listen to the cosmic piano every time we point a radio telescope, but instead of 88 keys, we’ll be using ten billion keys, with software designed to pick out any note with a frequency that is ringing consistently true against the background noise of all the other frequencies.”

Milner spoke of bringing a ‘Silicon Valley approach’ to SETI, one that will develop its own software tools using open source methods and maintaining open databases. Organizers estimate that what Breakthrough Listen generates will amount to the largest amount of scientific data ever made available to the public. Thanks to its open source nature, the software effort will be flexible enough to allow scientists and members of the public to use it and to develop their own applications for data analysis. As part of the crowdsourced aspect of Breakthrough Listen, Milner announced that the effort will join the SETI@home project at UC-Berkeley, in which nine million volunteers donate spare computing power to assist in the SETI search.

The project leadership team listed on the Breakthrough Initiatives site:

- Martin Rees, Astronomer Royal, Fellow of Trinity College; Emeritus Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics, University of Cambridge.

- Pete Worden, Chairman, Breakthrough Prize Foundation.

- Frank Drake, Chairman Emeritus, SETI Institute; Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and Astrophysics, University of California, Santa Cruz; Founding Director, National Astronomy and Ionosphere Center; Former Goldwin Smith Professor of Astronomy, Cornell University.

- Geoff Marcy, Professor of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley; Alberts SETI Chair.

- Ann Druyan, Creative Director of the Interstellar Message, NASA Voyager; Co-Founder and CEO, Cosmos Studios; Emmy and Peabody award winning Writer and Producer.

- Dan Werthimer, Co-founder and chief scientist of the SETI@home project; director of SERENDIP; principal investigator for CASPER.

- Andrew Siemion, Director, Berkeley SETI Research Center.

Image: Stephen Hawking addressing the audience at the Breakthrough Initiatives announcement. Credit: Breakthrough Prize Foundation.

As to the Breakthrough Message initiative, it should be stressed that it is not an effort to actually send signals to other stars. This last is an important point, so let me quote directly from the news release: “This initiative is not a commitment to send messages. It’s a way to learn about the potential languages of interstellar communication and to spur global discussion on the ethical and philosophical issues surrounding communication with intelligent life beyond Earth.”

The news of these two Breakthrough Initiatives comes on July 20, the day humans first landed on the Moon in 1969. Hawking noted the scope of the challenge. We already know that potentially habitable planets are plentiful, and that organic molecules are common in the universe. Intelligence remains the great unknown. While it took 500 million years for life to evolve on Earth, it took two and a half billion years to get to multicelled animals, and technological civilization has appeared only once on our planet. Is intelligent life, then, rare? And if it exists, is it as fragile and as prone to self-destruction as we ourselves?

“We can explain the light of the stars through physics, but not the light that shines from planet Earth,” Hawking said. “For that, we must know about life, and acknowledge that there must be other occurrences of life in an infinite universe. There is no bigger question. We must know.”

Small Interstellar Probes, Riding Laser Beams – The Project Dragonfly Design Competition Workshop

Today we look beyond Pluto/Charon toward possible ways of getting a payload to another star. Centauri Dreams readers are familiar with the pioneering work of Robert Forward in developing concepts for large-scale laser-beamed missions to Alpha Centauri and other destinations. But what if we go smaller, much smaller? Project Dragonfly, in progress at the Initiative for Interstellar Studies, proposes to explore this space, and as Andreas Hein explains below, it was recently examined in a workshop giving student teams a chance to present their ideas. A familiar figure in these pages, Andreas received his master’s degree in aerospace engineering from the Technical University of Munich and is now working on a PhD there in the area of space systems engineering, having conducted part of his research at MIT.

by Andreas M. Hein

The Project Dragonfly Design Competition, organized by the Initiative for Interstellar Studies (i4is) was concluded on the 3rd of July in the rooms of the British Interplanetary Society (BIS). To choose the rooms of the society is no coincidence. The BIS conducted the Lunar Lander study in the 1930s, which foreshadowed in an almost uncannily precise way the Apollo mission. Forty years later, in 1978, the BIS presented the first design of an interstellar probe: Daedalus. And in 2015, it was a natural choice to choose the BIS’ rooms for what might again be the stage for imagining things to come: Four international teams, almost exclusively consisting of students, are going to present their design for an interstellar probe. And this time, things get small.

Background

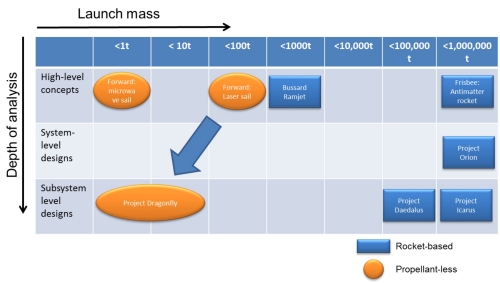

The field of interstellar studies can be divided into two categories. First, the field of interstellar studies is teaming with huge spacecraft, often as large and heavy as today’s largest skyscrapers. However, there is a second stream of concepts for interstellar spacecraft, beginning with Robert Forwards’ Starwisp probe and Freeman Dysons’ Astrochicken [1, 2]. These concepts stimulated thinking about the opposite: How small can we get? A small interstellar probe has a fundamental advantage. It needs less energy to accelerate to the same velocity. This is particularly relevant for interstellar missions, as we usually talk about required energies that often surpass current global energy consumption. Hence, any reduction in size might considerably increase the feasibility of an interstellar mission. Figure 2 shows an overview of some of the most relevant interstellar concepts and designs. The columns indicate the mass of a spacecraft from a particular concept or design in orders of magnitude. The rows indicate the level of detail. High-level concepts often consist of a basic feasibility analysis. System-level designs go deeper and describe key spacecraft systems in considerable detail. Subsystem-level designs add additional detail to all relevant spacecraft systems. The objective of Project Dragonfly is to address the gap in the lower left: To design an interstellar spacecraft down to subsystem level, ideally with a mass below 10 tons.

Figure 2: Some of the most relevant interstellar concepts and designs

The idea behind Project Dragonfly emerged in early 2013 when I visited Professor Gregory Matloff in New York. Greg is one of the key figures in interstellar research. That night we talked about different propulsion methods for going to the stars. We realized that nobody had yet done a design for a small interstellar laser-propelled mission. Soon after this conversation Project Dragonfly was officially announced by i4is. The name “Dragonfly” was chosen in order to pay credit to Robert Forward, who wrote the novel The Flight of the Dragonfly in the early 1980s, featuring a laser sail spacecraft. Later in 2013, i4is organized the “Philosophy of the Starship” Symposium at the BIS, where first presentations on laser-propelled interstellar probes were given by Kelvin F. Long and Martin Ciupa. Further vital preparatory work was done by Kelvin that year that fed into defining the competition requirements. With the first set of requirements defined, we finally got to the point where we were able to organize an international design competition in 2014. The purpose of the competition would be to speed up our search for a feasible mission to another star, based on technologies of the near future.

The Project Dragonfly Design Competition focused on small, laser-sail-propelled interstellar probes. Why small and laser-sail-propelled? In getting small, we are following a trend which started in the last decade. With the emergence of the CubeSat Standard first universities and then companies started to develop satellites, often not larger than a shoebox. Today, NASA and ESA are even thinking about sending small satellites to the Asteroids and Mars [3, 4]. However, the spacecraft still needs to be big enough to get enough science data back, setting a lower limit to spacecraft size, sufficient to host and supply power to the communication subsystem.

Why laser-sail-propelled? Laser sails are similar to solar sails. They both use light pressure for accelerating the spacecraft. Solar-sail-based spacecraft are today developed by various space agencies and organizations, from JAXA’s Ikaros mission to The Planetary Society’s LightSail 1. The elegance of solar sails is that they are scalable and use an abundant energy source: the Sun. Most types of solar sails could be used as a laser sail and vice versa. Hence, using a potential laser sail on a solar sail precursor would be possible in most cases. This would lower the barrier for testing a new type of sail, as operating a solar sail does not depend on a laser infrastructure.

Project Dragonfly leverages these two technology trends, as they seem to be promising to realize an interstellar mission in a scalable way.

The Project Dragonfly Design Competition

In August 2014, international university teams were invited to participate in the competition. All candidate teams had to submit solutions to a problem set first. This problem set included a range of small problems that were intended to train the teams in the key areas relevant for the competition, such as the basics of laser sail propulsion, laser systems, and in-space communication systems. The objective of this initial problem set was two-fold. First, it was intended as an entry barrier for all teams that do not have a serious intention or the capabilities to participate in the competition. Eliminating teams that would not make the cut later on also had the purpose of avoiding overburdening the reviewers. The reviewers we invited are very busy individuals. We wanted to use their time as effective as possible, giving them the opportunity to focus on the best teams. Second, the successful teams would be able to develop or strengthen their capabilities to solve the main competition task of designing a laser-sail-propelled interstellar probe. They would also get familiar with the existing literature on the topic and get a “feeling” for the subject.

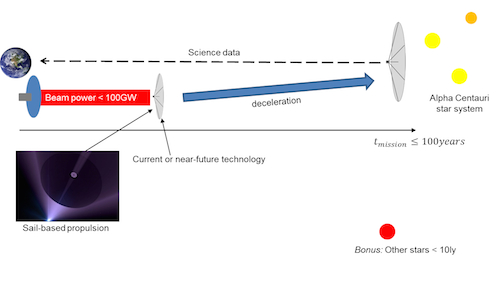

The teams that were able to pass this hurdle were then confronted with the mission requirements. These requirements used the requirements developed during Project Icarus as a starting point. Project Icarus is an ongoing collaborative interstellar study between the BIS and Icarus Interstellar, in which I am participating [5]. However, the requirements were adapted and extended to the laser sail case. The requirements are depicted in Figure 3 in a graphical fashion.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of the Project Dragonfly requirements

Written out, the mission requirements are:

1. To design an unmanned interstellar mission that is capable of delivering useful scientific data about the Alpha Centauri System, associated planetary bodies, solar environment and the interstellar medium.

2. The spacecraft will use current or near-future technology.

3. The Alpha Centauri system shall be reached within a century of its launch.

4. The spacecraft propulsion for acceleration must be mainly light sail-based.

5. The mission shall maximize encounter time at the destination.

6. The laser beam power shall not exceed 100 gigawatts

7. The laser infrastructure shall be based on existing concepts for solar power satellites

These requirements were deliberately fine-tuned in order to be challenging. The 100 GW beam power requirement constrains the design space considerably. The particular value was selected as it constrains the mass of the spacecraft to tens of tons. Furthermore, it is a beam power that is very challenging to generate with an in-space infrastructure within the 21st century but not completely out of reach. The 100 year time constraint sets a theoretical minimum average trip velocity of 4.3% of speed of light in order to reach the Alpha Centauri star system. With the power constraint only the spacecraft mass, its sail system parameters, and the duration of acceleration / deceleration are left as key variables. A long acceleration duration allows for reaching a high velocity. However, a long acceleration duration means that the laser beam has to be steered over long distances. This in turn makes pointing and focusing the beam challenging.

The science data requirement is also challenging to fulfill. If the teams decide to reduce the spacecraft mass, they need to shrink their communication system as well. However, communication over interstellar distances requires large amounts of power, if useful science data is to be collected and sent back.

The teams needed to navigate in this design space, making careful trade-offs between different parameters. The competition included two intermediate stage gates and a final review of the reports. Each stage gate required a different set of deliverables that are commonly required for concept studies in the space domain, such as an initial feasibility analysis, a technology readiness assessment, and detailed calculations for key aspects of the mission. The stage gate process allowed us to check and adjust our expectations for the next stage of the competition and provide targeted support if teams were struggling in a particular area. Furthermore, each of the deliverables covered a vital aspect that is commonly needed for a concept study. The staged approach enabled the teams to work on a limited set of deliverables at each stage, reducing the difficulty of the overall task.

The competition wouldn’t have been possible without our reviewers and advisors. Fortunately, we were able to recruit experts with considerable experience in solar and laser sailing studies, such as Les Johnson, who is working as the Deputy Director of the Advanced Concepts Team at NASA and Bernd Dachwald, a German professor.

Four international teams, out of initially six contestants were able to take all hurdles and submit a final design report:

Technical University of Munich

University of Cairo

University of California Santa Barbara

CranSEDS, consisting of students of Cranfield University, UK, the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology in Russia, and the Université Paul Sabatier in France.

These reports were this time graded by the reviewers. Furthermore, the teams were invited to present their designs at the final workshop in London, on the 3rd of July 2015.

The workshop

The main purpose of the workshop was to mimic a typical design review in the space sector. The teams would give a presentation, covering all vital aspects of their design and would then answer questions from the audience and review panel. The review panel consisted mostly of aerospace engineers. Notable members were the Executive Director of i4is, Kelvin F. Long, and Chris Welch, who is working as a professor at the International Space University.

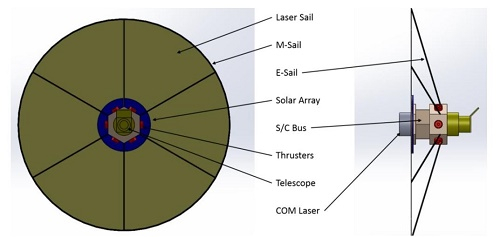

The first team to present was the team from the Technical University of Munich. Their spacecraft would be accelerated up to a distance of 2.2 light years and a velocity of 9% of the speed of light. The laser infrastructure would be placed on the Moon. Their laser sail would consist of a graphene sandwich material. Deceleration is enabled by a staged magnetic / electric sail. The team chose this staged approach, as the magnetic sail is very efficient at high velocities but gets increasingly less efficient at lower velocities. The electric sail is capable of decelerating at lower velocities. The spacecraft reaches the Alpha Centauri system after 100 years. Communication is enabled by a laser communication system. Power is supplied, either by solar cells that generate energy from the laser beam or the electric sail, which generates electric power when flying through the interstellar medium.

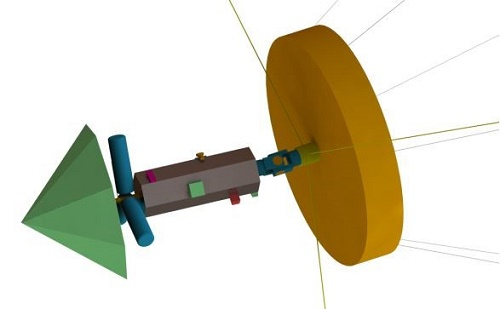

Figure 4: The spacecraft of the Technical University of Munich. Sail is not to scale.

The overall spacecraft is relatively heavy, compared to the other designs. It’s mass is 14t. Part of the reason is that the team aimed at maximizing the payload mass. A higher payload mass leads to a higher scientific yield but also leads to a heavier communication system, due to the higher data rate. Another effect is that a heavier spacecraft needs a longer duration to accelerate, imposing pointing requirements on the laser optics that are difficult to meet. Another difficulty with the overall architecture of the mission is that the laser system is located on the lunar surface. Although in principle feasible, installing such a system is very costly, unless a large amount of in-situ materials are used.

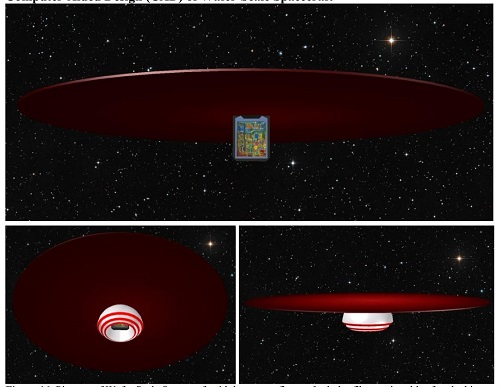

Figure 5: UCSB team wafer spacecraft design

The second presentation was given by the UCSB team. This team’s design combined the highest number of innovative technologies. It distinguished itself in numerous ways from the other teams. First, the concept of the spacecraft was a “wafer-based” design. This means that the spacecraft is basically imprinted onto a chip with all spacecraft subsystem integrated into it. The sail would consist of a dielectric material with an extremely high reflectivity, in order to withstand the enormous power density of several gigawatts per square meter. Note that sunlight in Earth orbit has a power density of about 1.4kW per square meter. Hence, the power density of the laser is roughly a million times higher than what today’s spacecraft are usually facing.

A highly reflecting surface avoids that part of the energy that is absorbed by the spacecraft, immediately melting it. The spacecraft is also accelerated rapidly, within a distance of three astronomical units, up to a velocity of 25%c. The team was able to consider such high velocities, as the spacecraft does not contain any deceleration system. Using deceleration systems such as a magnetic sail or an electric sail would lead to significant deceleration durations that may nullify any decrease in trip duration as a result of the high cruise velocity. However, the lack of a deceleration system does not comply with the mission requirements. The laser is a phased-array fiber-fed laser.

Figure 6: Samar Eldiary presenting the Cairo Team’s spacecraft

The third presentation was given by the Cairo University Team. The team’s mission design is based on an initial acceleration via laser beam, based on the DE-STAR system developed by the UCSB team. The spacecraft is decelerated via magnetic sail, and then separates into two sub-probes. One probe will collect data from Proxima Centauri, the other data from the Alpha Centauri A and B system. The laser sail is made out of aluminum. A laser communication system is used for sending back data to the Solar System. Power is provided by three Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs). The team presented an innovative approach for attitude control during the acceleration phase by changing the shape of the sail.

Figure 7: CranSEDS spacecraft design. The left image depicts the spacecraft bus with payload. The three cylindrical objects are the RTGs.

The last presentation was given by the CranSEDS Team. The interesting thing about their mission architecture is the use of a staged approach. A total of three spacecraft are launched within 33 year intervals. The rationale behind these intervals is to use each subsequent spacecraft as a communication relay station as well as exploiting technological advances that have occurred in the meantime.

First, the spacecraft is accelerated up to a velocity of 5%c at a distance of about 5,800 astronomical units. This phase takes about 3.7 years. The laser sail, used during acceleration, is then jettisoned. The subsequent cruise phase takes up to 77.5 years. Deceleration then starts via magnetic sail and the spacecraft enters the Alpha Centauri system after about 98 years of flight. 33 years after launch, a second spacecraft is launched with a similar configuration, but mission phases shifted by 33 years. The third spacecraft is launched after a similar interval of 33 years.

The team’s spacecraft is propelled by a Silicon Carbide sail. Power is provided by three RTGs. Data is sent back via laser communication. The overall mass of one of the spacecraft is about 4.5 tons. Each spacecraft hosts a scientific payload of 93kg, consisting of various instruments such as spectrometers, a magnetometer, and a cosmic dust analyzer.

The team presented detailed trade-off analyses for each of the critical aspects of the mission such as how many spacecraft to send and each of the spacecraft subsystems. The reviewers, however, remarked that the mission architecture, consisting of three separate spacecraft might induce programmatic risks, as the mission would need to be sustained over a period longer than a century. Furthermore, the so-called waiting paradox might come into play: A spacecraft launched later could overtake an earlier one due to a more sophisticated technology or laser infrastructure.

After the teams’ presentations, the review panel retreated for ranking the teams. As mentioned earlier, the team reports already contributed to the overall grading with two-third of the points. One-third would consist of the presentation and the teams’ performance during the Q&A session. After a few discussions, the review panel reached a conclusion and got back to the teams, waiting eagerly to hear the results.

Figure 8: The teams and members of the i4is leadership

We then announced the winners:

4. Cairo University

3. UCSB

2. CranSEDS

1. Technical University of Munich

The first prize, which went to the team of the Technical University of Munich, went along with one of the Alpha Centauri Prizes, which i4is awards to contributions advancing the field of interstellar travel.

Figure 9: Alpha Centauri Prize logo

Figure 10: The team from the Technical University of Munich (TUM) is awarded the Project Dragonfly Alpha Centauri Prize (left to right: Kelvin Long (i4is), Johannes Gutsmiedl (TUM), Nikolas Perakis (TUM), Andreas Hein (i4is))

After the ranking was announced, the next steps for Project Dragonfly were presented. First, the teams are requested to submit a summary of their report to a peer-reviewed international journal. The purpose is to receive another independent validation of the designs. Furthermore, the teams would gain experience in writing scientific publications. Another step is a technology roadmap, based on the technologies that were selected by the teams. Some of the technologies were common, such as laser communication and a magnetic sail for deceleration. However, the teams diverged in other technologies such as the laser sail material and power supply. With the teams, we will select key technologies and think about what steps are needed for developing them, along with prototypes and demonstration missions.

Later in the afternoon, the workshop participants gathered at the local bar and restaurant, the Riverside: A traditional gathering place after BIS events. Here, new friendships were forged between the participants and the future of Project Dragonfly was hotly debated.

Conclusions

The main conclusion is that a small, laser-sail-propelled interstellar mission is in principle feasible by using a laser infrastructure providing a 100GW laser beam. The Alpha Centauri system could be reached within 100 years. The spacecraft mass would be somewhere between 15 and a few tons. With the use of innovative technologies, even masses below one ton could be achieved.

The following conclusions can be drawn from the presented spacecraft designs:

- Laser communication seems to be a promising approach for achieving communication over interstellar distances.

- Magnetic sails seem to be the currently most promising way to achieve deceleration from velocities of a few percent of the speed of light.

- The trade-offs for the best laser sail material are non-trivial and there seem to be several promising materials.

- Most teams have used RTGs as power supply.

- More research needs to be done on the laser infrastructure. In particular, where to place it and how to leverage on potential future solar power satellite infrastructures.

However, there are several other feasibility issues that need to be addressed, such as beam pointing requirements over distances of several to thousands of astronomical units. Manufacturing and deployment of kilometer-sized solar sails is also an issue. Furthermore, spacecraft autonomy during the mission is a huge challenge as well. Deployment of magnetic sails with several kilometers in radius remains another feasibility issue.

Despite these challenges, let us not forget where we came from: Missions using the whole energy consumption of humankind. We were able to decrease that by two orders of magnitude or more. Yes, building such an infrastructure is an immense challenge but it is less a challenge than for example mining Jupiter for Helium 3 for two decades, as proposed for Project Daedalus, or harvesting large quantities of antimatter.

Maybe, and just maybe, some of the ideas presented during the workshop might one day open up the pathway to the stars. Until then, a lot of work remains to be done.

Let’s get started!

References

[1] Forward, R. L. (1985). Starwisp-An ultra-light interstellar probe. Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, 22(3), 345-350.

[2] Matloff, G. L. (2005). The incredible shrinking spaceprobe. Deep-Space Probes: To the Outer Solar System and Beyond, pp.61-69.

[4] Asteroid Impact Mission (ESA).

[5] Long, K. F., Fogg, M., Obousy, R., Tziolas, A., Mann, A., Osborne, R., & Presby, A. (2009). Project Icarus-Son of Daedalus-Flying Closer to Another Star. Journal of the British Interplanetary Society, 62, 403-414.

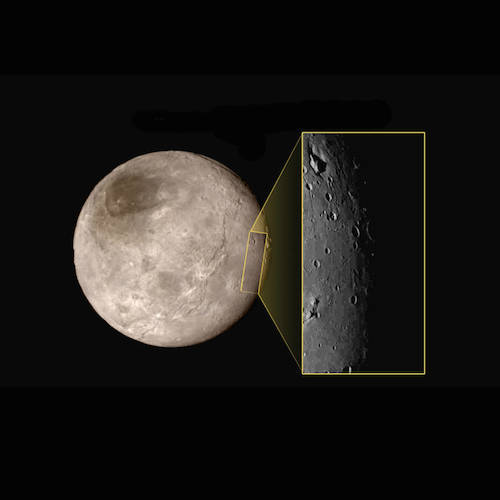

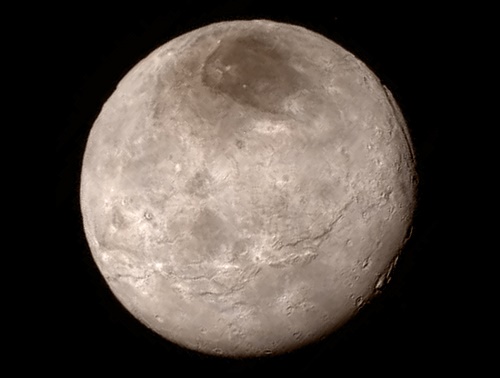

Unusual Charon Closeup

The latest view of Charon shows us a 390-kilometer strip of Pluto’s largest moon with a unique feature, clearly visible below. We are looking at what Jeff Moore (leader of the New Horizons Geology, Geophysics and Imaging team, calls “a large mountain sitting in a moat.” Moore is the first to admit that the scenario has geologists stumped.

Image: This new image of an area on Pluto’s largest moon Charon has a captivating feature — a depression with a peak in the middle, shown here in the upper left corner of the inset. The image shows an area approximately 390 kilometers from top to bottom, including few visible craters. Credit: NASA-JHUAPL-SwRI.

This view of Charon was taken at approximately 0630 EDT (1030 UTC) on July 14, 2015, about 1.5 hours before closest approach to Pluto, at a range of 79,000 kilometers. Again, notice the lack of craters here, reinforcing what we’re learning about Charon’s relatively young surface. I know we were all curious about Charon from the outset, but I don’t know anyone who thought we would be talking about geologically young features on either of these worlds. We have sharper versions coming — this image is heavily compressed, but the Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on New Horizons will be returning richer data.

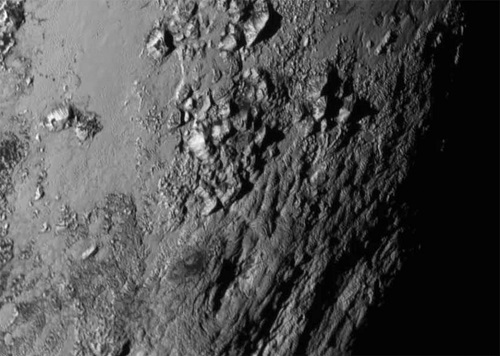

First Post-Flyby Pluto Imagery

I’m on the road and don’t have a lot of time for writing, but I want to go ahead and get these new Pluto images up. They’re now available on the NASA site, and were introduced at the news conference at JHU/APL that just concluded. I’ll also quote just a bit of the news release for each photo.

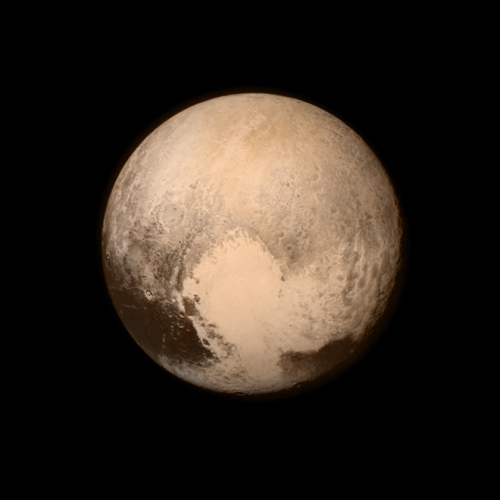

New close-up images of a region near Pluto’s equator reveal a giant surprise: a range of youthful mountains rising as high as 11,000 feet (3,500 meters) above the surface of the icy body.

The mountains likely formed no more than 100 million years ago — mere youngsters relative to the 4.56-billion-year age of the solar system — and may still be in the process of building, says Jeff Moore of New Horizons’ Geology, Geophysics and Imaging Team (GGI). That suggests the close-up region, which covers less than one percent of Pluto’s surface, may still be geologically active today.

This one I mis-typed in my Twitter coverage for those who were following it, but the correct number is 100 million years. Young mountains, and check that altitude! The lack of cratering implies a young surface, but we can rule out tidal effects as a driver for geology here. “This may cause us to rethink what powers geological activity on many other icy worlds,” says GGI deputy team leader John Spencer of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo.

Remarkable new details of Pluto’s largest moon Charon are revealed in this image from New Horizons’ Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI), taken late on July 13, 2015 from a distance of 289,000 miles (466,000 kilometers).

A swath of cliffs and troughs stretches about 600 miles (1,000 kilometers) from left to right, suggesting widespread fracturing of Charon’s crust, likely a result of internal processes. At upper right, along the moon’s curving edge, is a canyon estimated to be 4 to 6 miles (7 to 9 kilometers) deep.

Again, a relatively young surface shaped by geological activity. And note the diffuse boundary at the dark region at the north pole, suggesting we’re looking at a thin film of material. “Underlying it is a distinct, sharply bounded, angular feature; higher resolution images still to come are expected to shed more light on this enigmatic region.”

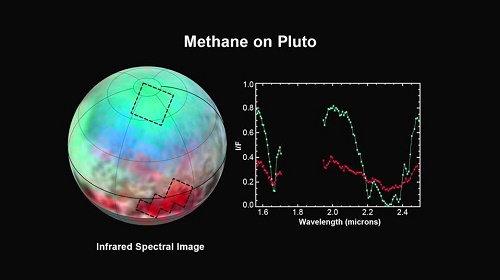

The latest spectra from New Horizons Ralph instrument reveal an abundance of methane ice, but with striking differences from place to place across the frozen surface of Pluto.

“We just learned that in the north polar cap, methane ice is diluted in a thick, transparent slab of nitrogen ice resulting in strong absorption of infrared light,” said New Horizons co-investigator Will Grundy, Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, Arizona. In one of the visually dark equatorial patches, the methane ice has shallower infrared absorptions indicative of a very different texture. “The spectrum appears as if the ice is less diluted in nitrogen,” Grundy speculated “or that it has a different texture in that area.”

We have so much data to come in the next sixteen months, and given the surprises we’ve already been dealt, it’s clear we’ll be talking about Pluto/Charon for some time. As one of the participants in the press briefing yesterday said, we’re not just re-writing the books now. We’re going to be writing entirely new books.

Pluto: Encounter and Aftermath

Exoplanet hunter Greg Laughlin (UC-Santa Cruz), who could make a living as a poet (if it were possible to make a living as a poet) wrote recently of his hope for a Pluto image ” that will become a touchstone, a visual shorthand for distance, isolation, frigidity and exile.” We haven’t seen that one yet, but I suspect we will with one of the images we’re still to receive showing New Horizons’ view of a receding crescent Pluto again being folded into the deep.

Last night’s reacquisition of the New Horizons’ signal sets us up for many weeks of data return, and provides a triumphant exclamation point on the flyby. Our spacecraft punched right through the orbital plane of Pluto’s system and emerged unscathed. The joy and festivity apparent on those actually at JHU/APL and the wild and celebratory conversations on social media bring home how popular this diminutive spacecraft has become. What an accomplishment, and even now I’m wondering what advances in technology could do in an outer system follow-up.

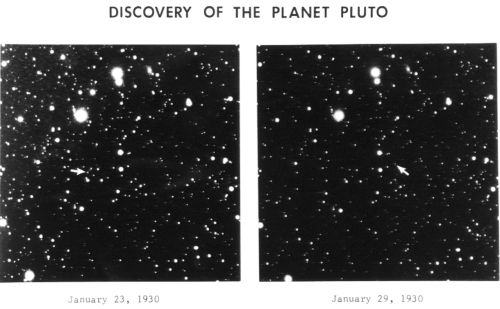

Clyde Tombaugh’s Apparatus

But I also found myself thinking of that portion of Clyde Tombaugh’s ashes that are now further from us than Pluto. Recently I mentioned Michael Byers’ fine novel Percival’s Planet (Henry Holt, 2010), which contains a fictional account of the discovery of Pluto, seen through the eyes of Byers’ protagonist, an astronomer named Alan Barber, who works with the same equipment Tombaugh uses. Weaving fictional characters in with historical personages like Tombaugh, Vesto Slipher and Percival Lowell, Byers re-creates the era and the task. Here he’s talking about the ‘blink comparator’ methods employed in the hunt for ‘Planet X’:

It is dreadful work, the blinking. You have two exposures of the same area of sky — long exposures a week apart or so; then the two exposed plates, ten inches square, are placed side by side in the big new Bosch, all brass fittings and an urgent smell of electricity and heated gas. Looking through an eyepiece you can see a very small portion of one of these plates — an area roughly the size of a nickel, showing about two hundred stars. Then you hit a switch and the comparator will show you the identical area of the other plate. And if you have managed against all odds to expose your two plates identically — if you’ve got the differential right, and the timing, and moreover if the weather hasn’t been hazy one night and clear the next, and if the telescope hasn’t slipped or jarred or just been slightly misaimed for some reason, and then if you’ve managed in the basement darkroom to develop both plates the same way — well, then you will see the same two hundred stars, looking the same way, appear again in the eyepiece as the blinker shows you the second plate.

The trick is to find a ‘star’ that vanishes or brightens or does something odd between one plate and another. You might be looking at a Cepheid variable, or you might find the track of an asteroid, or if you really get lucky, maybe you’ll find Planet X. Credit Clyde Tombaugh with a magnificent persistence. You can see from the discovery plates just how tricky this work was.

Next Steps in the Outer System

It was fifty years ago yesterday that Mariner 4 reached Mars, a fitting time to think about how far we have come and where we might go next. In What About the Next Pluto Mission?, Centauri Dreams regular Andrew LePage tackles the question of Pluto follow-ups, noting that given how infrequently we have low-energy launch opportunities, and considering the flight times necessary to reach Pluto, we should start thinking about an encore right now. We have a launch opportunity at the end of 2028 and the beginning of 2029 that LePage finds attractive. But there are other options depending on trajectory that he’s careful to analyze.

A follow-on mission, even a flyby, would benefit from advances in technology, remote sensing and miniaturization, allowing for more data to be collected, but LePage also speculates on the possibility of a design that would allow us to multiply our observing chances:

Depending on the available payload margin and, just as importantly, the new mission’s budget, it may prove possible to carry several lightweight but very capable sub-probes, with masses perhaps on the order of tens of kilograms, that the main spacecraft could deploy weeks or months before its 2039 Pluto encounter. These lightweight sub-probes could be directed to make observations of Pluto, Charon, or its other moons at closer range or under different viewing conditions than might be possible with the main spacecraft. This tactic would add flexibility to mission planning as well as the quantity and quality of the scientific data returned. While a traditional entry probe would be of little use in the thin atmosphere of Pluto (which has an estimated surface pressure on the order of a few microbars), a properly equipped sub-probe could be aimed to fly hundreds or maybe even tens of kilometers above Pluto’s surface to directly sample its atmosphere and any aerosol or cloud layers that may exist.

Moreover, there are various ‘energetically favorable’ launch windows in the early 2030s that could get flyby spacecraft to Uranus or Neptune, a follow-up to the grand work of the Voyagers. LePage suggests three separate missions to be launched toward Pluto, Uranus and Neptune in the 2028-2034 timeframe. Dedicated orbiters are, of course, the best choice for maximizing data return, but fast flybys give us the chance to get to the outer system again before any orbiters we choose to send arrive, which presumably wouldn’t be any earlier than mid-century.

The Allure of Sedna

Meanwhile, in At Pluto, the End of a Beginning, Lee Billings makes the case for renewed study of the outer system with his usual elegance. Even before we see the images and data we will be receiving over the next 16 months, we can take heart from the remarkable number of interesting features we’ve found:

Pluto bears a bright polar cap of methane and nitrogen ice, and mottled regions at its equator that signal strange and complex geology. Charon, by contrast, harbors a mysteriously dark polar region apparently bereft of bright ice, and an impact-generated chasm deeper and longer than Earth’s own Grand Canyon. More and better images will soon stream down from New Horizons’ far-distant memory banks, no doubt filled with even greater wonders – perhaps signs of ice volcanoes, or of ancient frozen seas, or of things so strange and unexpected they cannot yet be imagined. The only thing unimaginable is that they will contain nothing tantalizing enough to someday call us back.

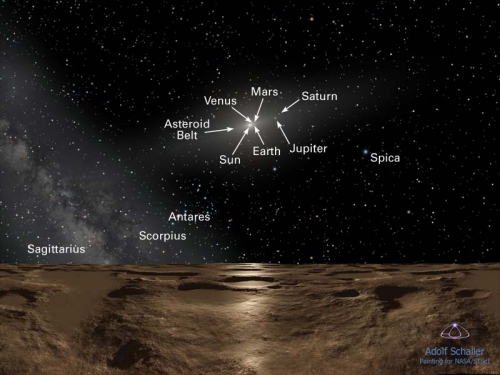

All the questions seem to be multiplying. Why is Eris more massive than Pluto, a question that resonates even as we debate whether or not Pluto may not in fact be a bit larger? Surely there are major differences in composition, but why did these occur? And on beyond Eris there remains the king of outer system puzzles. Sedna’s orbit, which goes out thirty times as far as Neptune’s at aphelion, seems to imply gravitational nudges from something else. Is there, Billings asks, a planet as large as several Earth masses waiting to be discovered? And we can add, is Sedna itself a capture from a primordial stellar flyby, an object from another star?

Image: An artist’s impression of the view from Sedna, with points of interest labeled. Credit: Adolf Schaller/NASA.

The questions abound, and we’ll start to tackle at least of few of them when New Horizons goes on to visit a Kuiper Belt Object, assuming an extended mission is approved (it’s hard to see it being rejected at this point). And closer in, we have only fragmentary looks at major satellite systems like those of Uranus and Neptune. Billings and LePage are pointing to what we need to be thinking about as we plan the next steps beyond New Horizons, a process that, given the length of time it takes to develop a mission and a spacecraft, we should have already begun.

Closest Approach!

Closest approach for New Horizons was at 0749:57 EDT (1149:57 UTC), with closest approach to Charon at about 0806 EDT. Mission operations manager Alice Bowman told the media briefing that we arrived at Pluto 72 seconds early and 70 kilometers closer than the aiming point, all of which was well within mission specs. Nice work.

I’ve found Twitter the best place to keep up, along with NASA TV for the media briefings. The #PlutoFlyby hashtag has been so active that it’s sometimes hard to read the messages, a heartening demonstration of the powerful sentiment this mission invokes. I also track @New Horizons2015, @NASANewHorizons, @AlanStern and, of course, @elakdawalla — Emily Lakdawalla’s work has been definitive. The Twitterverse has been exploding.

And here is the latest image, showing 4 kilometers per pixel, about 1000 times higher than Hubble can provide. Much better still to come. Here we’re sixteen hours from closest approach, at a distance of 766,000 kilometers. Note the varying areas of brightness, with very bright terrain just north of the equator. It’s a surface, says Alan Stern, that shows a history of impact and surface activity, but we have so much yet to learn as more data arrive.

The New Horizons team saw the image above for the first time this morning around 0545 EDT.

Image: Members of the New Horizons science team react to seeing the spacecraft’s last and sharpest image of Pluto. Credit: NASA / JHU/APL.

And now we wait. Stern estimates no more than two chances in 10,000 that we’ll lose New Horizons due to impact with debris, but until we get tonight’s signal, this writer at least is going to be on edge. After all, we’re crossing the orbital plane.