Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Project Persephone

Rachel Armstrong’s presentation at Starship Congress so impressed me that I was quick to ask her to offer it here. I’m delighted to say that it will be only the first of what will become regular appearances in these pages. Much could be said about this visionary thinker, but here are some basics: Dr. Armstrong is co-director of AVATAR (Advanced Virtual and Technological Architectural Research) in Architecture & Synthetic Biology at The School of Architecture & Construction, University of Greenwich, London, a 2010 Senior TED Fellow, and Visiting Research Assistant at the Center for Fundamental Living Technology, Department of Physics and Chemistry, University of Southern Denmark. She completed clinical training at the John Radcliffe Medical School at Oxford in 1991, and in 2009 embarked on a PhD in chemistry and architecture at University College London.

Perhaps only someone with this kind of diverse training could tackle the novel approach to building materials called ‘living architecture,’ that suggests it is possible for our buildings to share some of the properties of living systems. And clearly Dr. Armstrong is just the person to head Project Persephone, the Icarus Interstellar effort to conceive of worldship designs that are themselves living and sustainable for millennia, not so much artifacts as emerging entities that evolve over time even as they nurture their starfaring inhabitants. In what follows, Dr. Armstrong gives us a glimpse of arriving colonists adapting to a new planet and then moves on to describe how the worldships that carry them might function.

by Rachel Armstrong

“A world like ours, except for the emptiness.” Oliver Morton, 2003.

There is a small cluster of dwellings, on a watery planet way beyond this solar system, where pioneering explorers called Newmans, who have come down from the artificial moon, hang out. They are joined in their terraforming activities by oddlings who are not quite Newman – they have a more sprightly stride and a quicker eye for new signs of life. The Newmans have travelled across the centuries to establish themselves on the planet Gliese 581g. This was rather a mouthful, so they renamed it Nostalgia. Their first terraforming move was to sprinkle the precious dirt from their homeland into the planet’s atmosphere, which carried living seeds from their laboratory experiments. After decades, these creeping chemistries went ‘native’ with interesting results. Now slithering scoundrels flop, gaping out of the silt and flap tirelessly on the beach in an evolutionary race to gain a colonizing foothold on the hallowed dry land.

While the sentinels, who have only just evolved their magnificent tri-legs, which raise their skinny bodies out of the puddles, scream “no room!” and pick off the scoundrels in droves as they flail helplessly, in the effort to dry-dirt upgrade. But these frantic events make the planet sound like it’s teaming with life, when it’s not. Despite the sentinels’ protests, there is plenty of room. Yet the ecosystem is fragile and if it was not for the Newmans, it might have been a few billion more years before the carbon rich silt yielded any life forms at all. However, once loosed, the Newmans’ laboratory cultures have made a very good job of metabolising the dirt, and have literally, succeeded in eating themselves into existence. Every evening in the thirty-hour diurnal cycle, which is precision marked by the geyser clock, the Newmans stroll down to the brimstone lake and dip their bread with a giant spoon into the simmering waters, so they can feast upon the protein-rich pinworms that devour the succulent bait.

The pinworms have only one collective neurone that glows prettily when they swarm. But as lovely as their thin thoughts may be, they can weave no memory of the previous night’s feast. So the pinworm learn nothing about their fate and continue to devour the bread – made by the Newmans from flour that is carefully ground from the leftovers of pinworm feasts. Yes, it’s a strange place – but no stranger than the planet from which they hailed – a former blue, watery planet where the ice caps had long melted and the only remaining evidence there were ever oceans was a steam clogged atmosphere that never stopped spewing torrential rain.

The Humans, the evolutionary ancestors of the Newmans, built their worldship from space debris and fled their planet, which was in shockingly poor condition. The ship ripped itself from Earth’s orbit as the nuclear fusion engines were started and the already nostalgia-struck explorers rubbernecked for one last fleeting view of their home. They were expecting a memorable spectacle and were disappointed. The massive communications holofields gave them no farewell view of the pale blue dot of legend, but soiled their memories with a dirty, greyish mass – which was scarred by the creeping cracks of vast gullies, poisoned by leaking piles of toxic plastic and gnawed by flash floods. Indeed, these inhospitable conditions would drive the Humans that remained – to seek shelter as their world collapsed in an eyeless, subterranean existence.

But, of course, fantastic voyages to other worlds and what adventures they may hold, are as old as storytelling. Yet in the modern age we have access to technologies that enable us to write our dreams beyond the world of stories and transcribe our imaginations into physical forms. It is impossible to say which leads – reality or our imaginations – since the two are so tightly coupled that philosophers are unlikely to ever need to worry about their own obsolescence. And yet, surfing the tidal time wave of change not only requires agile thinking and the capacity to act upon it – but also relies on our ability to think beyond our conventions and customs. At the start of this millennium we have adopted a condition of comfortable familiarity and Romantic idealisation of our resources on earth. Under the self-regulating gaze of Gaia these, rather magically, never ‘really’ get old, run out or even poison us – an irony indeed as our industrial processes turn our cherished idylls into the toxic landscapes that are ‘not quite fatal’, described by Rachel Carson.

While futurists look to the horizon, or scan the blue sky for solutions to the conditions faced by humanity in the 21st century, they seldom seek to explore the black sky for insights and boldly probe the possibilities of the completely unknown. Indeed, some consider interstellar exploration a folly when there are more immediate problems to fix using our tried and tested approaches. Yet, when these established methods are actually part of the problem itself, it is time to take Einstein’s advice and step outside of our comfortable cognitive space that gave rise to the problems in the first place and plunge into the abyss of black sky thinking – not as a self-destructive act – but a creative tactic to uncover fertile terrains that may inform the choices and actions of our current and future generations, both on Earth and amongst the stars.

Yet if we are to conceptually and physically leave the planet for the sake of human advancement and expansion, then we first need to consider what it means to be ‘earth bound’. Earth bound is a term used by Bruno Latour to describe humans that recognise the Earth’s ecology as being integral to their identity. Earth bound therefore depicts a cultural condition for those generations that are always heading for earth, as they are unable to escape its materiality and its laws. In interstellar terms, we are earthbound, being tied to and shaped by our materiality and seeking other habitable earths that will promote our survival. Perhaps we may even carry our native terrestrial soils with us, so we may flourish in lands way beyond our origins.

I am project leader for Persephone, which is one of the Icarus Interstellar projects that catalyse the construction of a crewed interstellar craft within a hundred years – and responsible for the design and implementation of a living interior to the worldship. Although the details of Icarus Interstellar have not been formalised, the ideas that I will share with respect to the design and engineering of Persephone, are best suited to a Slow, Wet Worldship. You may even imagine this soggy interior as being in a very physical sense, ‘alive’. If it is to survive interstellar travel over evolutionary timescales, which may exceed a thousand years – then it will need to gather resources from extra terrestrial sites. But, where do you start in designing and developing a ‘living’ interior for such a vessel? The vital technologies for a worldship do not depend on mechanical systems alone but also soft, nature-based ones – like the ones, for example that encircle the outer surface of our own planet – which carry out useful work through metabolism – and challenge our notions of ‘control’ through their innate agency. Indeed, for a living system to be sustained, it needs to be kept from reaching equilibrium.

In other words, the design and engineering priorities are to preserve flow and flux – rather than maintaining the integrity of a hierarchical series of objects, as in the case of machines. But once living systems are established within a niche environment, they bring many unique features that increase survivability – such as, robustness, flexibility, the ability to deal with unexpected events, the capacity for propagation and the propensity to adapt and evolve, even when there is a relatively limited flow of exchange, as in a troglodyte cave. In thinking about evolutionary timescales, they are most frequently depicted in space operas as modifications of current humans and machines, where the surroundings – the living spaces in the worldship – may be taken as a constant. But in space, the fate of the earthbound is tightly coupled to more than just their machines. When they evolve, it is with their whole ecology – and while we do not factor this in for a terrestrial setting, it may be critical to take a holistic view for long term space colonization. Persephone therefore aims to deal with worldship habitats as extended human ecosystems and as a point of reflection on our current ecological challenges.

Perhaps you have recently heard someone observe that the human body is 90 percent bacteria. These collections of microbes are called the human ‘biome’ and they appear to be critical to our health, nutrition and even in regulating our moods. While we consider these relationships as being symbiotic in a terrestrial environment, we have no idea what happens to them over prolonged time periods in a worldship – especially as bacteria evolve much faster than we do. Well, not quite no idea – the Salmonella pathogen has been shown to increase its virulence 3 to 7 times under reduced gravity in the ISS, as the result of ‘fluid shear’ which makes the bacteria think they’re inside a gut.

However, from an ecosystems perspective, Persephone is also aware of the difficult task it faces as the new kid on the block in the challenging legacy of biosphere design.

Richard Buckminster Fuller, viewed the earth as a ‘well-provisioned ship, on which we sail through space’ – a neatly, cling film wrapped, pale blue dot – surrounded by a dark, murky universe – that is separated from the cosmic fabric by its exalted earth-ness. But David Deutsch has criticized Fuller’s lyrical idea of Spaceship Earth as a harmonious habitat, afloat in a barren cosmos – as being difficult to defend, even metaphorically. In only 4.5 billion years our sun will become a bad tempered red-giant, prone to cosmic fits of ill temper that will swallow us whole. Deutsch echoes Darwin’s view of the world, governed by a Nature that is ‘red in tooth and claw’ – and while it creates – it is also ready to tear our world apart.

The first real effort to create a terrestrial ‘ark’ to demonstrate that careful management alone can produce functional ‘closed systems,’ was the Soviet BIOS-3 series of experiments that ran from 1972 to 1984. They supported a community of three people supported with an algal cultivator and a ‘phytron’ where sunlight was simulated to grow wheat and vegetables. While BIOS-3 demonstrated that chlorella algae could produce oxygen and that it was possible to recycle up to 85% of the water in the system, it was not a ‘closed’ biosphere. Dried meat and energy were provided from external sources and human waste was stored instead of being recycled back into the system.

The mission was attempted again with Biosphere 2 in the 1990s that aimed to understand how people in close confines, in a closed ecological system could work together over a sustained period. Yet, it was quickly clear that despite being equipped with a desert, rainforest, and ocean – it was going to be very difficult to create a sustainable environment. Oxygen levels steadily fell, the ocean acidified, internal temperatures rose, CO2 levels fluctuated, vertebrates and pollinating insects died, while the crew became depressed, dysfunctional and malnourished. Only the cockroaches and ants thrived.

Of course, there is nothing ‘sustainable’ about closed systems, despite McDonough and Braungart’s success with promoting their industrially friendly Cradle-to-Cradle approach. The truth is that closed systems, with living things in them – are coffins – and will ultimately grind down to an entropic halt. Regardless of the attractive view that Fuller paints of our world, Earth is not and has never been a closed system – it gets external energy, lots of it, from the sun and is constantly bombarded by cosmic rays, one of the sources of mutation and variation in our DNA. Yet, for those who would like to insist that the earth is closed because ‘effectively’ no matter leaves the planet – other than the notable exceptions of space telescopes, robots, kilograms of bacteria and piles of space junk – it is perhaps worth remembering Einstein’s equation E=mc2. This elegant concept describes matter and energy as different versions of the same thing. So, in physical terms – our planet being soaked in sunlight – can be regarded as receiving a continual flow of matter.

Indeed, the Earth receives many cosmic packages in a more familiar material form as meteorites, asteroids and cosmic dust. Our planet is being rained on from space. The majority of meteors that bombard the earth are little more than particles of dust. Larger ones enter the earth’s atmosphere and rapidly burn up to form small meteors, and micrometeorites. Ten thousand tons of this extra-terrestrial shrapnel falls on the earth every day. Admittedly the more spectacular large-scale material payloads are no longer so frequent in the vacuum of space that they’re abundant – but they are not THAT rare in the history of the earth. Indeed, Paul Davis notes that earth’s oceans were leftovers from intense asteroid bombardment during the Hadean period. And earlier this year an asteroid exploded over the region of Chelyabinsk in Russia bringing its heavenly gifts of destruction, mayhem and a smattering of weakly magnetic, radioactive rocks.

My point is that in proposing a ‘living’ interior for a worldship, which contains living things – the system needs to be imagined and designed as an open system – or our worldship will become the universe’s most beautifully designed and best travelled compost heap. Yet, even if we can build a worldship to operate within an ‘open’ cosmic system that can munch on cosmic foods such as, electromagnetic spectra and dirty asteroids – there is an even a deeper issue to address, which relates to the way we design and engineer with lifelike systems.

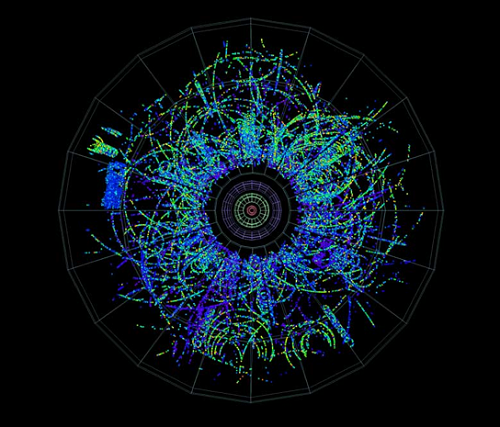

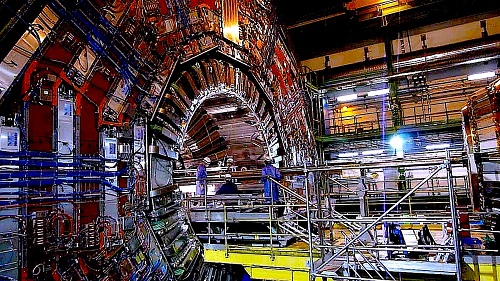

In 1948 Erwin Schrodinger noted that the characteristic of life is that it resists the decay towards entropic equilibrium. This observation is profoundly important when thinking about the design of an environment for living things, as it requires us to consider far-from equilibrium conditions as the substrate for our interventions. This flies in the face of all our design efforts to history, because when we design, we generally assume that our surroundings are at equilibrium and therefore we are engaged in making a world of objects. Yet, if we look at the very large and very small scales of existence, this object-centred version of reality does not hold true. When the atom was split last century, strange subatomic particle worms were released into reality and our imaginations – as leptons, bosons and hadrons. And when we dive down into the nature of these massless specks of matter, they are anything but still, existing as probabilistic clouds of nearly nothingness. Their essence is so primitive that they do not exist in nature and can only be experienced in the most indirect way of ‘seeing’ anything ever.

In the biggest Swiss watch ever made – the Large Hadron Collider – a whole particle superhighway is dedicated to evidencing the imperceptible. Buried 100 metres underneath the Swiss/French border, the LHC viewing platforms orchestrate miniscule Ballardian fantasies by smashing primordial plasma streams, of hydrogen and lead ions, into one another. As the particles shatter in layers upon layers of thick sensate materials, sophisticated algorithms interpret their screams from the wreckage and translate them into digital visualizations. And once you’ve witnessed the screams of a particle dying, how can anything around you ever be still again?

In building a new world, Persephone is invoking the existence of a new nature and if we are to design a space that supports dynamic systems, then we must learn to effectively design at non-equilibrium states – and create environments with material flows, whose cultural equivalent is dirt. Design hates dirt – as it is aesthetically and materially subversive. Yet the various forms of dirt – such as, shit, grit and dust – when combined, have powerful transformative potential.

In space, shit is surprisingly useful.

Dennis Tito’s ship will protect its astronauts from cosmic radiation using food and water, which contains more radiation absorbing atoms than metal. And since organic matter blocks rather than absorbs the radiation, it apparently also remains safe to eat. The lucky married couple’s excrement will gradually replace these larder supplies during their round-trip to Mars scheduled for 2018. Yet, practical development of the concept is needed so Tito’s space honeymooners, and generations after them, don’t find themselves in a round trip to a sub standard hotel in Benidorm, full of unpleasant sights and smells. However, these concepts add ecological depth to the idea of space travel. More than 90 percent of wastewater can be recovered using membrane-filtering techniques – and indigestible fiber in human faeces can be transformed into a material that resembles an adobe brick wall. Greenhouse gases – namely carbon dioxide, methane gas and water vapor – can also be harvested. While these processes are not cost effective in short-term missions, in long-term missions – where systems are effectively closed – these approaches are increasingly valuable. Therefore when building for worldship interiors, it is worth remembering that all civilizations are founded on their relationship with the potent transformer that we call soil.

Persephone’s first task is to identify her native soils – to transform and develop them into subjects worthy of design – exquisite stuff – that is not simply a life-support system – but provides the very context and meaning for living processes. Soils are a living web of relationships within complex bodies that will eventually grow old and die. Plants take root in the rich chemical medium and bind the particles together to attract animal life. Conversely, soil harbors fungi and bacteria that break down the bodies of dead creatures and turns them into more soil. The speed of this dynamic conversion process varies. In fertile areas it may take fifty years to produce a few centimeters of soil but in harsh deserts it can take thousands of years. Soils are biological cities. They house, nourish and provide the vital infrastructure for terrestrial life, which laid the foundations for the establishment of ecosystems, the evolution of humans and the construction of the built environment. The rich complexity of soil systems provides a model and literal substrate for a built environment that can self-maintain and connect with ecological systems.

On the face of it – it may appear a straightforward thing to grow a soil – like we might construct a building. Soil scientists observe how we can mix the various particles, adjust the acidity, compost the organic substrate and bring these inorganic and organic worlds together. But making a soil is more than measuring ingredients for a recipe, they are composed of matter that possesses the vibrancy and vivid hues of the rainbow, embody the poetry of symbiosis – and perhaps most importantly – they are our binding contract with Nature.

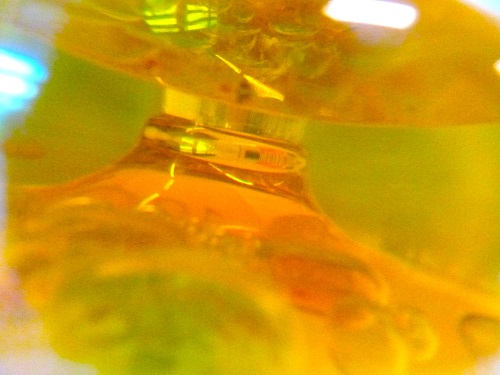

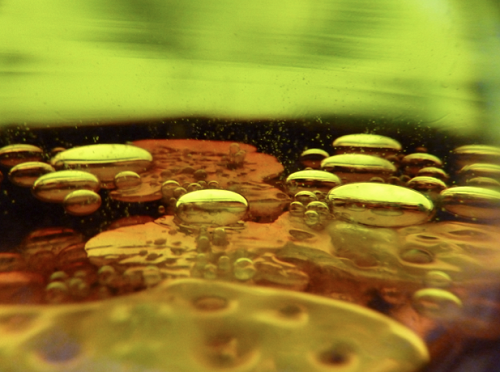

But how may we forge a contract with Nature in space, where no native biology is known to exist – only physics and chemistry. Over the last few years, I have been working with living chemistries and synthetic biologies, shaping materials that possess a will and exert a force of their own, independently of a central program or my design and engineering intentions.

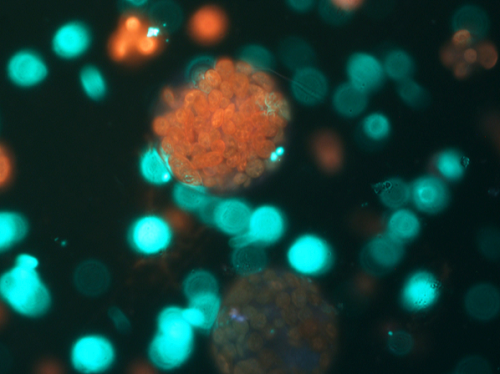

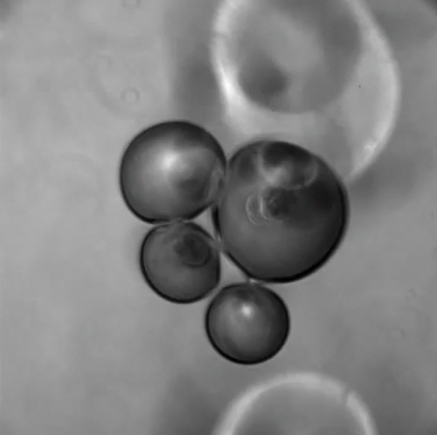

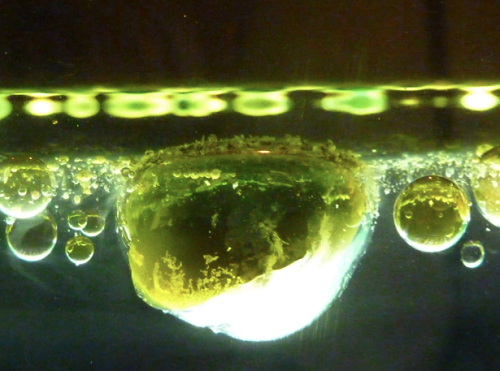

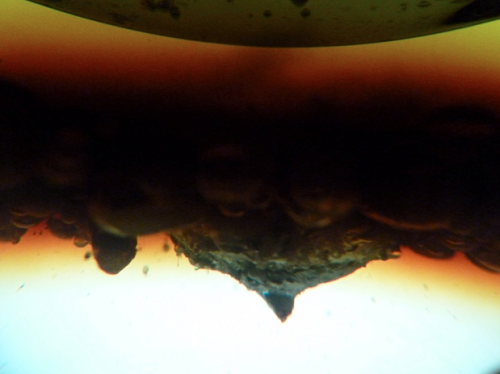

These materials have formed primitive, dynamic cell-like structures – or protocells.

I have been able to clump these primitive chemical assemblages into oily vessels to punctuate a cybernetic, hylozoic ground where they fixed carbon dioxide from gas hungry solutions.

I have used gravity to infiltrate gel-like matrices that creep towards the ground, producing Liesegang bands of chemical separation and reconciliation.

And I have exploited the relentless splitting of crystals into rhizomatous mucous fronds, which lengthen and grow when entangled with carbohydrate polymers.

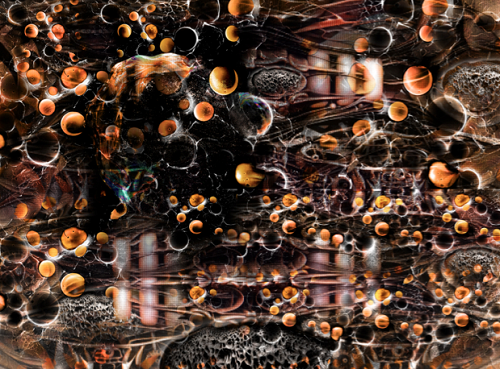

Persephone proposes to create her soils, before she even contemplates the possibility of ‘life’, by applying the physical and chemical principles of their native environment. She aims to develop an architectural practice of natural computing – a term inspired by Alan Turing’s interest in the computational powers of Nature – to produce a new kind of spontaneously self-organizing and autopoietic system that is unique to the worldship. Persephone will harness the creativity of particle worms and develop their connections at different scales using the parallel processing power of chemistry to create a condition of fertility that, within definable limits of probability, may give rise to its own life-like events.

Soil is a probabilistic matrix that is peppered with events and flows, within which life is not inevitable – but increasingly feasible. It inserts time and space into chemical systems so that the potent conditions are delayed from reaching equilibrium and happen again and again and again. Soil hosts many chemical events that arise from the horizontal coupling between dynamic systems. It may give rise to living things by facilitating chemical assemblages such as, Stuart Kauffman’s autocatalytic sets. It offers a fertile field in which living things are anthropogenically midwifed into existence by farming technologies. Yet, while life is the event by which we may measure the success of soils, it is the product of a multitude of partnerships that form the heaving, squirming mass of soil bodies. Soils are the site of huge amounts of metabolic work, which shape the muck that decides whether ecosystems will thrive and ultimately, produces the conditions that give rise to cities.

And here, Persephone’s challenges begin. Although this presentation began with a story, the project itself is real and fully intends to go ‘beyond’ fiction, proposing that the way of opening up new worlds is first through the imagination, where uncertainty is a driver for radical creativity in a probabilistic, cosmic landscape – the Black Sky.

Whatever the odds of Persephone’s success in her endeavours, she is aware that she will not triumph because of the odds – but in spite of them. Indeed, the only way to guarantee her – and our own extinction – is simply to take our continued existence for granted and hand over control to the ants and cockroaches, without trying anything new, or daring at all.

——-

And now, the oddlings looked up to the sky under the green reflected light of their artificial moon – simply called Newman. Sometimes they could see the stars twinkling between the cracks in its regolith and asteroid shell and at other times they wondered how things might change when the other Newmans came down to settle Nostalgia’s surface. But each night, little changed. The pinworms continued to swim brainlessly in the brimstone, the scoundrels floundered and the sentinels wrapped their long necks around their tri-legs, as they settled down for ten long hours sleep before the dawn broke – and all the metabolic slithering started again.

——-

“They will not be a new story’s beginning, rather the creation of a new chapter. Their expectations and hopes are already being created on the Earth today …” Oliver Morton, 2003.

On Brown Dwarfs and Other Exotica

Knowing the position of a firefly within one inch from a distance of 200 miles would not be easy, but it’s the kind of precision astronomers Adam Kraus and Trent Dupuy needed when trying to establish the distance of nearby brown dwarfs. The firefly simile belongs to Kraus (University of Texas at Austin), who with Dupuy (Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics) embarked on a study of the initial sample of the coldest brown dwarfs discovered by the Wide-Field Infrared Survey Explorer satellite (WISE). Their paper appears today is Science Express online.

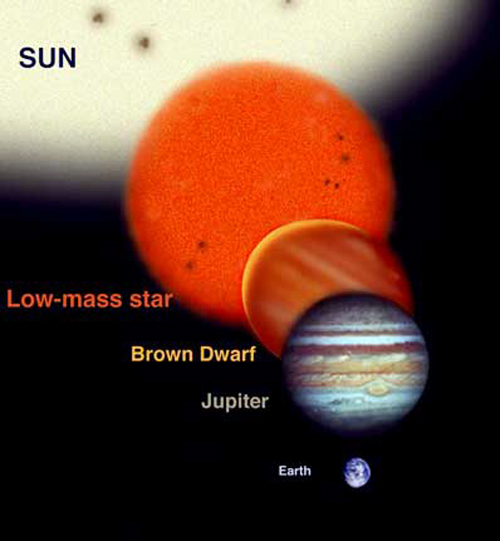

Image: Brown dwarfs in relation to more familiar celestial objects. Credit: Gemini Observatory/Jon Lomberg.

Just how cool can brown dwarfs get? When we’re focusing on small dwarfs somewhere between 5 and 20 times the mass of Jupiter that have been cooling for billions of years, we’re talking about objects whose only source of energy is gravitational contraction, and as Dupuy notes, the fine-grained distinctions between star and planet begin to get blurred here: “If one of these objects was found orbiting a star, there is a good chance that it would be called a planet.”

So what does make the difference? The key determinant is that brown dwarfs formed on their own rather than in a proto-planetary disk. Moreover, they’re exceedingly hard to characterize because most of their light is emitted at infrared wavelengths and their small size and low temperature make finding them tricky. The astronomers, in Dupuy’s words, “wanted to find out if they were colder, fainter and nearby or if they were warmer, brighter and more distant.”

To answer these questions involved measuring their distance accurately. For that, the duo turned to the Spitzer Space Telescope and put parallax methods to work on the nearby brown dwarfs previously identified by WISE. We’ve often discussed parallax in these pages as the method used to make measurements of stellar distance, a feat first accomplished by the German astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel in 1842 with his work on 61 Cygni — Bessel’s reading of 10.3 light years wasn’t all that far off the now accepted value of 11.4 light years.

The early days of parallax in astronomy (and there were 60 stellar parallaxes in the literature by 1900) involved observing a star from one side of the Sun’s orbit and then, half a year later, the other, looking for the slight changes that would make the calculation possible. In the case of Kraus and Dupuy’s work with the Spitzer instrument, the needed precision was mind-boggling but measurable, enough to determine that the objects in question range between 20 and 50 light years away.

The upshot: Brown dwarf temperatures in the range of 395 to 450 K (250 to 350 degrees Fahrenheit), allowing them to retain their status as the coldest known free-floating celestial bodies but making them a bit warmer than some earlier studies have suggested. These objects cool slowly over time, their heat produced by contraction rather than fusion. Recent work has suggested that brown dwarfs could sustain habitable conditions for tightly orbiting planets for several billion years. I mention this because yesterday we saw in the work of Mukremin Kilic that planets in certain configurations around white dwarfs could have eight billion years of habitability.

What lies ahead is the great hunt to discover whether worlds like these actually exist. What a time to enter exoplanet studies — a theme we keep encountering is that habitable conditions may exist around stars far different from our Sun. M-dwarfs first opened our eyes to this but brown and white dwarfs push us into whole new realms of investigation as we try to learn how frequently planets can form around them and whether any might have astrobiological possibilities. Not so long ago we assumed that other solar systems would look more or less like ours. Now we look into a cosmos filled with exotica and ask whether we’re not the outliers.

For more on brown dwarf planets and habitability, see Andreeshchev and Scalo, “Habitability of Brown Dwarf Planets,” Bioastronomy 2002: Life Among the Stars. IAU Symposium, Vol. 213, 2004 (abstract), as discussed in Brown Dwarf Planets and Habitability. See also this Astrobiology Magazine feature on why white and brown dwarf planets may not be capable of sustaining life (thanks to David Cummings for the reference to this one).

A White Dwarf Proposal for Kepler

With four years of collected data at hand, Kepler scientists will remain busy even with their spacecraft hobbled. We now know that we’re not going to get Kepler back to full working order following the degradation of two of its reaction wheels, but as this report noted on August 19, possibilities remain for scientific studies using the two remaining reaction wheels aided by thrusters to control the spacecraft’s attitude. And as we’re finding out, a ‘two-wheel’ Kepler mission may still offer opportunities, one of the more fascinating of which is our subject today.

The proposed target is white dwarf stars, the remnants of stars whose mass is not high enough to produce a neutron star as they evolve past the red giant phase. A typical white dwarf has a mass similar to that of the Sun, but a volume close to that of the Earth. While Sirius B, at 8.6 light years out, is the closest known white dwarf, eight white dwarfs are believed to be present among the one hundred closest star systems to the Sun. And while we don’t normally think of white dwarfs as capable of sustaining life-bearing planets, maybe we should take another look. A new paper points out that stars like these can provide an energy source for billions of years.

Image: A white dwarf as compared with the Earth. Credit: Ohio State University/Richard Pogge.

To orbit in a white dwarf’s habitable zone requires an orbit in the range of 0.01 AU for temperatures that could support liquid water on the surface to exist. This is a habitable zone that evolves with time, starting off too hot for liquid water and eventually becoming too cold to sustain it, but surprisingly, a white dwarf planet in this kind of orbit could have a maximum of eight billion years of habitability to support whatever life might form there. Lead author Mukremin Kilic (University of Oklahoma) and team calculate an overall habitable zone extending from 0.005 AU to 0.02 AU.

Could such planets exist? Clearly, an expanding red giant will consume its inner planets before contracting into a white dwarf, so planets within 1 AU or less will presumably have to arrive after the red giant phase. But possibilities exist: We’ve found planets orbiting close to the exposed core of a red giant (KOI 55.01 and KOI 55.02) and we’ve even found planets around pulsars. There are models that produce short period planets in billion-year timescales that seem to be applicable to white dwarfs, with planet formation from nearby gas being one scenario and the capture or migration of planets from much further out in the system being another.

Add delivery of water through cometary impacts and the presence of a habitable world in either scenario seems a bit less unlikely. We can also throw into the mix the fact that 30 percent of the white dwarfs near the Sun show metal-polluted atmospheres perhaps caused by the accretion of rocky debris. Indeed, some 4.3 percent have known debris disks, the latter a demonstration that interactions within the system can send asteroids, moons or small planets close to the white dwarf. But if short-period planets around these stars do exist, we have yet to find them, a fact the paper attributes to our lack of observational data for a sufficient number of stars.

Kilic and team argue that Kepler in its two-wheel mode offers an opportunity to run the kind of survey that would find the first exoplanets in a white dwarf habitable zone. From the paper:

If the history of exoplanet science has taught us anything, it is that planets are ubiquitous and they exist in the most unusual places, including very close to their host stars and even around pulsars (Wolszczan & Frail 1992). Currently there are no known planets around WDs, but we have never looked at a su?cient number of WDs at high cadence to ?nd them through transit observations. It is essentially impossible to ?nd Earth-Jupiter size planets around WDs by any other method (Gould & Kilic 2008). If habitable planets exist around WDs, the proposed Kepler imaging survey will ?nd them.

The proposed survey would require 200 total days of observing time examining 10000 white dwarfs in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey imaging area, the great benefit being that Kepler’s wide field of view would allow a large number of white dwarfs to be observed at the same time. The researchers believe up to 100 planets will be identified in the habitable zone, an extension of the Kepler planet-hunting charter extended to a new set of targets. The paper continues:

Biomarkers, including O2, on such planets can be detected with the JWST [James Webb Space Telescope]. Hence, even though this is a completely unexplored search area for transiting planets, the scienti?c yield of the proposed survey will be enormous.

Exactly so. Remember this about white dwarfs as transit targets. The stars are about the same size as the Earth, so Earth-sized and smaller planets should be easy to detect as they pass in front of the primary. And once a planet in the habitable zone has been identified, the high contrast ratio between the planet and the host white dwarf means that future telescopes should be able to run the biomarker searches mentioned above. Is it possible that the first evidence of life on an exoplanet may come not from a G- or even an M-class system, but a white dwarf?

The paper is Kilic et al., “Habitable Planets Around White Dwarfs: an Alternate Mission for the Kepler Spacecraft,” a Kepler white paper available as a preprint. For more on white dwarf planets, see Habitable Worlds around White Dwarf Stars. Thanks to Antonio Tavani for the pointer to this work.

Thoughts on Ceres (and Memories of Pohl)

Working on this entry last night, I found my thoughts turning inescapably to Frederick Pohl, the iconic science fiction writer and editor whose death was announced just hours ago. Most Centauri Dreams readers doubtless have their memories of Pohl’s work, perhaps from the great novels of the 1950s like The Space Merchants and Gladiator-at-Law or the striking Gateway of the late 1970’s that would spawn the Heechee series. As something of a bibliographer, I’m also fascinated with Pohl’s role as a youthful magazine editor. He was editing Astonishing Stories for the pulp house Popular Publications at the age of 20, an occupation that would deepen into lengthy runs at Galaxy and IF and later stints editing books for Bantam.

Pohl’s early days in science fiction are captured memorably in The Way the Future Was, a 1978 reminiscence that had me digging through my collection of old pulps to look up issues he had edited. Astonishing was always a favorite of mine, but I was surprised to realize how fond he must have been of Super Science Stories, which he oversaw from 1939 to 1943. In fact, one of Pohl’s last blog entries this July was an exhortation to bring back Super Science Stories in a new format, basing it on reprints much like the late Famous Fantastic Mysteries created by the Munsey group in the 1940s.

“I know I shouldn’t give it a thought, but if an offer got real, how could I say no?” Pohl wrote, not six weeks before his death. I would have loved to have seen that revived magazine in his hands.

But back to business. I learned of Pohl’s death while drawing up some notes on the asteroid belt, with which Pohl will always be associated in my mind because of the Heechee novels, in which some asteroids turn out to have been the site of an incomprehensible alien technology. The juxtaposition seemed utterly appropriate, for I remember reading Gateway in 1980 and thinking that Pohl had deftly sidestepped the interstellar propulsion conundrum. Rather than spending centuries developing the technologies to make a star mission happen, maybe we just run across an artifact that does things we can’t explain and makes such journeys possible. A thousand starships are at Gateway for the asking, though how they work is a mystery. I wouldn’t dream of throwing in any spoilers here, so you’ll have to go to the novels for more.

Ceres Inside and Out

What a grand notion the Heechee novels represented. It’s a shame Pohl won’t be here two years from now when the Dawn mission finally reaches the dwarf planet Ceres, which may hold a few surprises of its own. Orbiting in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, Ceres is nonetheless much closer in composition to Jupiter’s moon Europa than to the rocky debris around it, particularly from the standpoint of astrobiology. Is it in fact a closer, easier Europa? This article in Astrobiology Magazine offers some thoughts on what Dawn mission science team liaison Britney Schmidt calls “a game changer in the Solar System.”

The change in nomenclature from asteroid to dwarf planet is indicative of the changes in our view of this object over the decades. When astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi discovered it in 1801, the object seemed inevitable, for as early as 1596 Johannes Kepler had noted the gap between Mars and Jupiter, and Johann Bode would later point to the probability of finding a planet there. The hypothesis of a pattern in planetary orbits like this has now been discredited, but the discovery of Uranus in 1781 seemed to confirm it and Ceres would be found shortly thereafter. As more and more asteroids began to be discovered and the true size of Ceres was realized, it lost the planetary status it had been assigned for almost half a century in astronomy books.

There’s no need to go back into the 2006 debate about what constitutes a planet other than to say that Ceres has now emerged as a ‘dwarf planet,’ joining Eris, Haumea, Makemake and Pluto in the designation. Confusingly enough, Ceres is still referred to as an asteroid in many quarters, though its unique status is conveyed in its round shape, an indication of formation in the early Solar System. The wild card, of course, is that there is the potential for a layer of water ice under the surface. Twice the size of Enceladus, Ceres is less than three times as far from the Sun as the Earth, making it a tempting target for studying water’s history as our system evolved.

Given the surface of objects like our own Moon, we can assume that Ceres has withstood its share of impact events in the early days of the Solar System, but an icy surface could have simply erased the evidence. Spectral evidence is also informative. From the article:

“The spectrum is telling you that water has been involved in the creation of materials on the surface,” Schmidt said.

The spectrum indicates that water is bound up in the material on the surface of Ceres, forming a clay. Schmidt compared it to the recent talk of minerals found by NASA’s Curiosity on the surface of Mars.

“[Water is] literally bathing the surface of Ceres,” she said.

In addition, astronomers have found evidence of carbonates, minerals that form in a process involving water and heat. Carbonates are often produced by living processes.

The original material formed with Ceres has mixed with impacting material over the last 4.5 billion years, creating what Schmidt calls “this mixture of water-rich materials that we find on habitable planets like the Earth and potentially habitable planets like Mars.”

I think Schmidt makes a good point, too, in going on to argue that Ceres may be just as interesting as more distant moons like Europa and Enceladus. For one thing, while Europa taps tidal interactions with Jupiter as a source of heat, Ceres draws on the Sun. For another, it’s considerably warmer than Europa, and unlike the latter, is not bathed in Jupiter’s deadly bands of radiation. Orbital or lander operations on Ceres should pose fewer challenges than Europa. What sets Europa apart, though, is the probability of a liquid ocean, while Ceres’ water is most likely in the form of water ice located in the mantle that wraps around its solid core.

Image: Scientists using the Hubble Space Telescope found Ceres was more like a planet than an asteroid — information that eventually led to a change in its categorization from asteroid to dwarf planet. Ceres’ mantle, which wraps around the asteroid’s core, may even be composed of water ice. The observations by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope also show that the asteroid has a nearly round shape like Earth’s and may have a rocky inner core and a thin, dusty outer crust. Credit: NASA/ESA/SWRI/Cornell University/University of Maryland/STSci.

I’ll return to the science fiction theme by mentioning that Larry Niven’s Known Space stories posit an asteroidal government based on Ceres, while the dwarf planet also appears in various roles in the hands of writers from Alfred Bester to Robert Heinlein and, in recent days, James S. A. Corey. The Dawn mission will presumably not find any Pohl-style gateways among the asteroids, but what an opportunity Ceres presents. In 2015, five months of Dawn’s orbital operations there will turn a fuzzy image into sharply resolved surface features in the same year that New Horizons does the same for Pluto/Charon. Ceres may reshuffle our thinking if we learn that it once had the potential for habitability. What we won’t have, alas, is Frederick Pohl’s fictional take on what a human mission to Ceres might look like and the wonders it might find.

Upcoming Interstellar Events

The quickening pace of interstellar conferences in the past couple of years has been an encouraging surprise. If one necessary goal is to energize the public about the human future in space, then these meetings and their media coverage are surely part of the picture. I’m thinking about adding a calendar feature for conferences and other interstellar events to Centauri Dreams. Until then, here are some upcoming items, presented in chronological order.

“The Starships ARE Coming”

Peter Schwartz, writer, futurist and co-founder of the Global Business Network, will present a talk about starships and the scenarios that could lead to them on September 17th at 7:30 in San Francisco. Coordinated by the Long Now Foundation, the talk will track Schwartz’ presentation at the recent Starship Century conference in San Diego. From the Long Now site:

Participants included scientists such as Freeman Dyson and Martin Rees and writers such as Gregory Benford and Neal Stephenson. The professional futurist in the group was Peter Schwartz, who contributed scenarios playing out four futures of starship ambitions. To his surprise, exploring the scenarios suggested that getting effective star travel over the coming century or two is not a long shot. Even by widely divergent paths, it looks like a near certainty.

Schwartz’ talk “The Starships ARE Coming” will be presented at the SF Jazz Center in San Francisco. For more, click here.

100 Year Starship 2013 Public Symposium

The Orlando conference that kicked off the DARPA solicitation in 2011 is fondly remembered for its scope and depth, not to mention its sheer size. Now that the Dorothy Jemison Foundation for Excellence has formed the 100 Year Starship organization, we’ve had last year’s conference in Houston and anticipate an upcoming event in the same city. From the symposium website:

Across the globe, calls are being made for bolder human expansion into space beyond earth orbit. Achieving the interstellar journey in many ways must build upon, promote and establish fundamental research, technology development, societal systems and capacities that facilitate ready access to our inner solar system and which will leave an indelible mark upon life on earth. 100YSS is working to create new avenues to foster such innovative, robust collaborative, Transdisciplinary research, project design and technological development. The 100YSS 2013 Public Symposium—Pathway to the Stars, Footprints on Earth—seeks to highlight both the small incremental steps and radical leaps required to make significant progress on the way to interstellar space.

The 2013 Public Symposium runs from September 19-22 at the Hyatt Regency Downtown Houston. For details and registration, go here.

Conversation with Gregory Benford

Physicist and science fiction writer Gregory Benford will appear at the Crawford Family Forum for a public conversation with KPCC’s Mat Kaplan, host of a science series called “NEXT: People | Science | Tomorrow.” Kaplan is also a host for the Planetary Society’s Planetary Radio. From the KPCC website:

Our ancestors gazed at a night sky filled from horizon to horizon with brilliant stars. Were they dreaming of reaching for the cosmos even before they were fully human? Regrettably, interstellar voyages with today’s technology would take thousands or even tens of thousands of years. We’re not there yet, but some of the smartest people on our planet are working on ways we can conquer the final frontier. Propulsion by energy beam, warp drive and other technologies are being researched with encouragement from NASA and other organizations.

“NEXT: Is This the Starship Century?” will take place on Wednesday September 25 from 7:00 to 8:30. For more information, click here. The Crawford Family Forum is at 474 South Raymond Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91105.

Second Starship Century Symposium in London

The second Starship Century Symposium will be held Monday October 21 at the Royal Astronomical Society on Piccadilly in London, with Royal Astronomer Martin Rees as a featured speaker. Including talks and a panel, the event will feature both James and Gregory Benford, editors of the recently published Starship Century anthology, which will be sold on the premises (proceeds going toward interstellar research). I should also mention that those of you who have asked about ebook editions of Starship Century can now find it online with color illustrations at Amazon, Smashwords and Barnes & Noble. Admission to the symposium is free.

The schedule for this event is still being firmed up, but speakers will include astronomer Ian Crawford and Stephen Baxter (tentative), with a starting time of 10:00 AM.

Gravity Design Challenge

And although it’s not interstellar in nature, I do want to mention a competition of the sort I hope we’ll see more of in relation to space themes. Science education non-profit Iridescent is partnering with Warner Bros. Pictures in what is called the Gravity Design Challenge, based on the upcoming George Clooney/Sandra Bullock film Gravity. The film, due out in October, is a survival tale set in low-Earth orbit. Iridescent is hosting the Gravity Design Challenge on Curiosity Machine, its online science studio. The idea is that teenagers will work with their parents to create what Iridescent calls a ‘Rube Goldberg Machine rocket’ that simulates a space mission.

The month long contest is ongoing and ends September 10. The grand prize winner receives a trip to New York and four tickets to the premiere of Gravity. From an Iridescent news release:

Volunteer mentors, including professional engineers, faculty and students from a variety of organizations, including Boeing, Columbia University, Stanford University, UC Berkeley, USC, and University of San Francisco, will provide feedback to Gravity Design Challenge participants through the submission period. A panel of experts from the astrophysics field will judge the final entries.

The idea of leveraging popular entertainment in the direction of science education is one that could prove fruitful as a way of nudging young minds toward careers in aerospace, just as science fiction itself does. There are all kinds of creative ways this might be accomplished on the Net, and we’ll see whether future media events can tap into a similar educational impulse.

Existential Risk and Far Future Civilization

How do we ensure the survival of our civilization over future millennia? Yesterday Heath Rezabek discussed installations called Vessels that would contain both archives and habitats to offset existential risk. Today Rezabek’s collaborator, author Nick Nielsen, broadens the view with an examination of risk itself and three possible responses for protecting our culture. Nick is the author of two books, The Political Economy of Globalization (Palgrave Macmillan, 2000) and Variations on the Theme of Life (Trafford, 2007). In addition to his recent talk at Starship Congress in Dallas, he presented “The Moral Imperative of Human Spaceflight” in 2011 at the 100 Year Starship Symposium in Orlando, and “The Large Scale Structure of Spacefaring Civilization” at the 2012 100YSS conference. In addition, he authors two blogs: Grand Strategy: The View from Oregon and Grand Strategy Annex, focusing on the future of civilization and the philosophical implications of contemporary events. Mr. Nielsen is a contributing analyst with Wikistrat, an online strategic consulting firm.

by J. N. Nielsen

To see our world as a pale blue dot barely visible in the vastness of space graphically shows Earth’s place in the universe, and if we could continue to expand our scope for several more orders of magnitude while remaining focused on our pale blue dot, we would perceive our Earth in the full magnitude of its cosmological context. Just as Earth is placed in cosmological context in its appearance as a pale blue dot, we must similarly place earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization in its cosmological context, and we can do so by way of astrobiology. Astrobiology can be considered an extrapolation and extension of terrestrial biology, or as biology in a cosmological context.

There are many definitions of astrobiology, some quite detailed and others quite concise. The NASA strategic plan of 1996 (quoted in Steven J. Dick and James E. Strick, The Living Universe: NASA and the Development of Astrobiology, 2005) gives this definition of astrobiology:

“The study of the living universe. This field provides a scientific foundation for a multidisciplinary study of (1) the origin and distribution of life in the universe, (2) an understanding of the role of gravity in living systems, and (3) the study of the Earth’s atmospheres and ecosystems.”

The NASA astrobiology website characterizes astrobiology as follows:

“Astrobiology is the study of the origin, evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. This multidisciplinary field encompasses the search for habitable environments in our Solar System and habitable planets outside our Solar System, the search for evidence of prebiotic chemistry and life on Mars and other bodies in our Solar System, laboratory and field research into the origins and early evolution of life on Earth, and studies of the potential for life to adapt to challenges on Earth and in space.”

More briefly, astrobiology has been called, “The study of life in space” (Mix, Life in Space: Astrobiology for Everyone, 2009) and that, “Astrobiology… removes the distinction between life on our planet and life elsewhere.” (Plaxco and Gross, Astrobiology: A Brief Introduction, 2006). Taking these sententious formulations of astrobiology as the study of life in space, which removes the distinction between life on our planet and life elsewhere, gives us a new perspective with which to view life on Earth.

With earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization placed in cosmological context, we ourselves and our civilization can be understood in terms of the Fermi paradox. Fermi asked, if the universe is filled with life, “Where is everybody?” The universe is billions of years old, demonstrably compatible with the existence of intelligent life, and yet we find no evidence of highly advanced civilizations. The paradox has only been sharpened by recent scientific discoveries of exoplanets, including small, rocky planets in the habitable zones of stars, some of them relatively nearby in cosmological terms.

Once we remove the distinction between life on earth and life elsewhere we see that the idea of an “alien” is an anthropocentric concept, and a Copernican conception such as astrobiology must do away with the idea of “aliens” as constituting all life other than earth-originating life. So when we ask, “Where are all the aliens?” We must answer, “Right here, on earth; we are the aliens.”

A conception of intelligence and civilization as comprehensive as astrobiology would place these phenomena in cosmological context, and drawing on the insights of astrobiology we can see that an anthropocentric conception of alien intelligence as all intelligence other than earth-originating intelligence limits our conception of intelligence, as an anthropocentric conception of alien civilization as all civilization other than earth-originating civilization limits our conception of civilization. A Copernican conception will be concerned with the fate of life, intelligence, and civilization as such, but we must also acknowledge that we are all that is known so far of life as such, uncopernican though that sounds.

We are the only known “aliens” to pass through the Great Filter – which is what we call whatever it is that has filtered out other possible civilizations in the universe and left us only with our own civilization on Earth – and the development of astrobiology has directed our attention to the many near disasters we have experienced in the past – disasters that have shaped the surface of our planet and the history of life on Earth. The emergence of a single hominid species from several branches of hominid evolution makes homo sapiens a kind of existential choke point or bottleneck in the history of intelligent life, so that there is a sense in which we are the great filter. And this life, which is itself a marvelous and meaningless accident of the cosmos, is vulnerable at any moment to being annihilated by another meaningless accident of the cosmos.

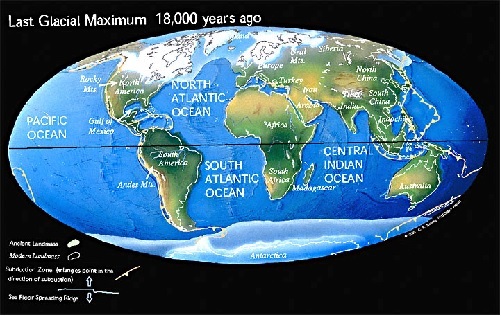

Through the ages of cosmological and geological time our homeworld has been subject to massive volcanism, asteroid impacts, solar flares, gamma ray bursts, and the extensive glaciation that characterizes the present Quaternary glaciation, with its warmer inter-glacial periods such as the Holocene, during which the whole of human civilization has emerged. These natural forces of the Earth, the solar system, and the cosmos at large have shaped terrestrial life, humanity, and human civilization; we have been hammered on the anvil of a violent and dynamic universe. And we have survived thus far, but our survival is not guaranteed.

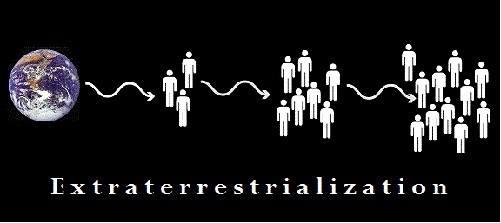

Earth-originating life has now given rise to industrial-technological civilization, which continues in its development to this day. What follows planet-bound industrial-technological civilization is the process of extraterrestrialization – the movement of the infrastructure of terrestrial civilization off the surface of the Earth and into space – which places earth-originating civilization in cosmological context, just as the pale blue dot places Earth in cosmological context and astrobiology places life in cosmological context. The process of extraterrestrialization, should it come to pass, furnishes us with a more comprehensive conception of civilization that begins to transcend our anthropic bias.

The resources of industrial-technological civilization hold the promise that life, intelligence, and civilization can spread beyond our terrestrial homeworld. Each stage in the development of a civilization capable of harnessing the energy resources required to expand beyond exclusively planet-bound conditions represents passing through further layers of the Great Filter. The gravitational thresholds of our home world, our local solar system, our local galaxy, and our local universe are each of them existential risks and existential opportunities for the future development of earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization. With the passage beyond one gravitational threshold to another, existential risk is mitigated but not eliminated; the mitigation of one level of existential risk means ascending to a more comprehensive level of existential risk.

The technology that our civilization develops will influence the structure of extraterrestrialized civilization. If the settlement of the universe is parallel to the settlement of our planet, each gravitational threshold will first be passed by an initial slow wave, only to much later be filled in by faster waves of expansion resulting from later, higher technology. But in the event of a disruptive technological breakthrough, as, for example, any of the technologies based on the Alcubierre drive concept, there could be an initial fast wave of expansion only later filled in by slower and more thorough later waves filling in the gaps.

Given extraterrestrialized civilization in its cosmological context, we can approach existential risk mitigation through three principles: knowledge, which transforms unknown uncertainties into quantifiable risks that admit of calculation and mitigation, redundancy, which means multiple self-sufficient centers for Earth-originating intelligent life, and autonomy, which assures the independence of each self-sufficient center to seek its own strategies for survival.

What does knowledge have to do with risk? Following economist Frank Knight, what we call Knightian risk distinguishes between predictability, risk, and uncertainty, with predictability implying total knowledge, risk implying partial knowledge, and uncertainty implying the absence of knowledge. These are simplified and idealized categories; no risk is entirely free of uncertainty, and even uncertainty must lie within what is possible within our universe, and in that sense is predictable. But Knightian risk offers a framework to think about the dynamic nature of risk, which changes over time. The growth of knowledge moves the boundary of risk outward, meaning less uncertainty and more predictability.

For example, even if we have done very little in the past forty years in terms of human space exploration and extraterrestrial settlement, and we are still accessing earth orbit with disposable chemical rockets, space science has made enormous progress during this period of time, and this knowledge has transformed our understanding of our universe and our place within it. This growth of our knowledge of the universe has made the universe a little less uncertain and a little more predictable for us, suggesting clear paths for the management and mitigation of existential risk.

Knowledge alone is not enough. Without redundancy of earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization we still face the possibility of a terrestrial single-point failure. Existential risk mitigation ultimately means multiple self-sufficient centers for Earth-originating intelligent life. These distinct centers of earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization will be subject to distinct risks and distinct opportunities, and these distinct populations of Earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization will be subject to distinct selection pressures, so that they will evolve into unique forms.

Knowledge of risks and redundant centers of earth-originating life together are not yet enough to secure on the long-term viability of Earth-originating life, intelligence, and civilization. Redundancy without diversity incurs the risk of homogeneity and monoculture. Existential risk mitigation also points to the necessity of the independence of each self-sufficient center to seek its own strategies of survival. The mutual independence of self-sufficient centers means the possibility of continued social and technological experimentation, which will in turn lead to the realization of distinct forms of civilization.

Autonomy seems like a simple enough condition, but it may be more difficult to achieve than we suppose. If we look around the planet today, with all its ethnic and cultural diversity, we see that there is, for all practical purposes, only one viable form of political organization – the nation-state – and again, for all practical purposes, only one viable form of civilization – industrial-technological civilization. We need to proactively seek to transcend social and technological monoculture to arrive at a civilizational pluralism from which social and technological experimentation flows naturally.

Taking existential risk seriously means that certain moral imperatives follow from this perspective, but who would possibly object to preventing human extinction? Of course, it is not as simple as that. It might be more difficult than we suppose to define human extinction, because to do so we would need to agree upon what constitutes human viability in the long term. Additionally, there are vastly different conceptions of what constitutes a viable civilization and of what constitutes the good for civilization. What is stagnation? What is flawed realization? What exactly is subsequent ruination, when achievement is followed by failure? What constitutes a civilizational failure? What exactly would constitute the “drastic failure of… life to realise its potential for desirable development”? What is human potential? Does it include transhumanism? For some, transhumanism is a moral horror, and a future of transhumanism would be a paradigm case of flawed realization, while for others a human future without transhumanism would constitute permanent stagnation. These are difficult questions that cannot be wished away; to pretend that they are not contentious is to fail to do justice to the complexity of the human condition.

These different conceptions of human potential and desirable outcomes for civilization will issue in different ideals, different aspirations, and different actions, but if we can continue to increase knowledge, establish redundancy and assure autonomy there is reason to hope that existential catastrophe can be avoided and an OK outcome realized, which is the point of what Nick Bostrom calls the maxipok rule – maximizing the probability of an OK outcome, where an OK outcome is defined as an outcome that avoids existential catastrophe.

If we do nothing, we will have on our conscience the extinction of all earth-originating life, intelligence and civilization. In the long term, our survival is only to be had through the extraterrestrialization of our civilization. But survival is not salvation. Survival often simply means that we will have the opportunity to go on to make later mistakes on a larger scale, which constitutes an OK outcome that is better than the alternative.