Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Probing a Brown Dwarf’s Atmosphere

The American Astronomical Society’s meeting in Long Beach is going to occupy us for several days, and not always with exoplanet news. Brown dwarfs, those other recent entrants into the gallery of research targets, continue to make waves as we learn more about their nature and distribution. The hope of finding a brown dwarf closer than Alpha Centauri has faded and recent work has emphasized that there may be fewer of these objects than thought — WISE data point to one brown dwarf for every six stars. But habitable planets around brown dwarfs are not inconceivable, and in any case we are continuing to build the census of nearby objects.

The latest from AAS offers up what could be considered a probe of brown dwarf ‘weather.’ If the idea of weather on a star seems odd, consider that the cooler brown dwarfs are far closer to gas giants than stars, unable to trigger hydrogen fusion and gradually cooling as they age. That means cloud patterns form and huge storms plow through the various atmospheric layers. At AAS, Daniel Apai (University of Arizona) presented the results of work on the brown dwarf 2MASSJ22282889-431026, which he conducted with a team led by the university’s Esther Buenzli. The results are useful not just for brown dwarf study but planetary atmospheres as well.

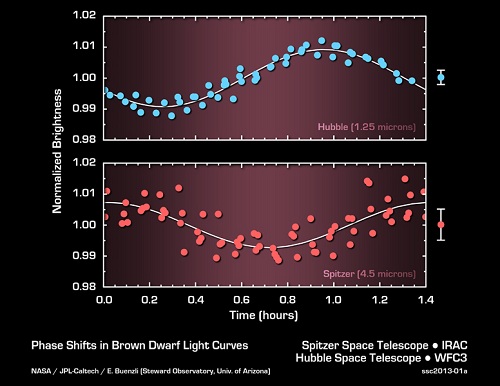

Using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes simultaneously, the researchers found that every ninety minutes the light from the star varied as it rotated. Because they were looking at the object at different wavelengths, they were able to see that the timing of the brightness change depended on wavelength. Some infrared wavelengths emerge from deep within the star, while others are blocked by water vapor and methane at higher altitudes. What we’re getting, in other words, is a look at layers of material being carried around the brown dwarf in likely storms.

But these aren’t your usual clouds, according to Mark Marley (NASA Ames), a co-author on the paper:

“Unlike the water clouds of Earth or the ammonia clouds of Jupiter, clouds on brown dwarfs are composed of hot grains of sand, liquid drops of iron, and other exotic compounds. So this large atmospheric disturbance found by Spitzer and Hubble gives a new meaning to the concept of extreme weather.”

The brown dwarf in question is cool in stellar terms but still hot enough — 600 to 700 degrees Celsius — to produce clouds like those Marley describes. The light variations offer the researchers a chance to understand the brown dwarf’s weather in the vertical dimension. Another scientist involved in the work is Adam Showman, also at the University of Arizona, who notes: “The data suggest regions on the brown dwarf where the weather is cloudy and rich in silicate vapor deep in the atmosphere coincide with balmier, drier conditions at higher altitudes — and vice versa.”

Image: This graph shows the brightness variations of the brown dwarf named 2MASSJ22282889-431026 measured simultaneously by both NASA’s Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes. As the object rotates every 1.4 hours, its emitted light periodically brightens and dims. Surprisingly, the timing, or phase, of the variations in brightness changes when measured at different wavelengths of infrared light. Spitzer and Hubble’s wavelengths probe different layers in the atmosphere of the brown dwarf. The phase shifts indicate complex clouds or weather patterns that change with altitude. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech.

A way forward in brown dwarf studies is suggested in the paper:

We have measured longitudinal variability throughout the near-infrared in a T6 dwarf and found an unusual correlation of light curve phase with the pressure probed by a given wavelength, which suggests a complex horizontal and vertical atmospheric structure. Our observations should provide an incentive to drive the development of higher-dimensional atmospheric models in order to gain a deeper understanding of dynamical and radiative processes in brown dwarf and exoplanet atmospheres.

Hubble and Spitzer are thus giving us the ability to probe a brown dwarf atmosphere in ways that, according to Apai, are not dissimilar to how doctors probe the body with medical imaging techniques. The unexpected offset between the different layers of atmospheric material tells us that a feature we might see on the surface of a brown dwarf may have shifted as we push into the inner layers of the object. That’s a sign of wind-driven clouds in constant motion, a warmer version of features like Jupiter’s Great Red Spot on an object not quite planet, not quite star.

The paper is Buenzli et al., “Vertical Atmospheric Structure in a Variable Brown Dwarf: Pressure-dependent Phase Shifts in Simultaneous Hubble Space Telescope-Spitzer Light Curves,” Astrophysical Journal Letters 760 (2012), L31 (preprint).

Earth-Sized Planets Widespread in Galaxy

Plenty of interesting news is coming out of the American Astronomical Society meeting in Long Beach CA, enough that I’ll want to spread our look at it out over the next few days. I want to start with Geoff Marcy’s investigations with grad student Erik Petigura at UC-Berkeley, the two working in tandem with Andrew Howard (University of Hawaii) on the question of Earth-sized planets and their distribution in the galaxy. But I can’t help noting before I begin how science fictional all these exoplanets are starting to seem as each day brings a new paper or announcement.

For me, science fiction has always been as much about landscape as it is about science, and exoplanets are the ultimate exercise in imagining exotic places. When exoplanet announcements were still new and we had only a small catalog of these worlds, I would find myself pondering each and thinking about what it would be like to orbit one, or stand on it. Now we’re getting hard data on potentially habitable places that evoke the compelling artwork on the covers of SF magazines I’ve read over the years. People gripe about not having flying cars or humans in the outer system, but to me the future I’ve lived into is every bit as provocative as the one that used to be portrayed in the pages of Astounding or Galaxy.

I spent yesterday afternoon thinking about the upcoming presentation of Marcy’s team at the AAS. They’ve created a new structure within which to analyze Kepler photometry for transiting planets, applying their algorithm to a sample of 12,000 G and K-class stars that were chosen because they are among the most photometrically quiet of Kepler’s targets, and thus best suited for the detection of small planets. The work focused on close-in planets with orbits between 5 and 50 days, Earth-sized worlds that are at the margin of detectability within the Kepler data.

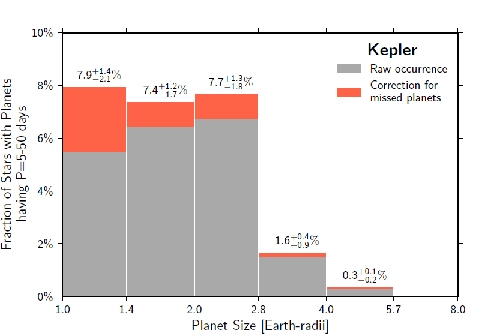

The results show that about 17 percent of all Sun-like stars have planets in the 1-2 Earth diameter range orbiting close to their host stars — here we’re talking about distances within about 0.25 AU, which places these worlds well inside the orbit of Mercury. The team also extrapolates from its results that the fraction of stars having planets of Earth size or a bit bigger orbiting in Earth-like orbits may be as high as 50 percent. Both findings follow from the researchers’ analysis of how often planets of a particular size appear, as Andrew Howard notes:

“Our key result is that the frequency of planets increases as you go to smaller sizes, but it doesn’t increase all the way to Earth-size planets — it stays at a constant level below twice the diameter of Earth.”

In other words, there are more small planets than large ones, with perhaps one percent of stars having planets the size of Jupiter, while 10 percent have planets the size of Neptune. But Petigura’s work goes farther than this, suggesting that the increase in planets as size decreases stops when we get down to planets of about twice Earth’s diameter. The numbers then remain the same until we reach planets the size of the Earth, beyond which this analysis ends. That’s a finding that leaves plenty of room for Earth-like worlds in abundance throughout the galaxy.

Petigura’s work was clearly key for the project because it was he who developed TERRA (Transiting ExoEarth Robust Reduction Algorithm), a program through which the UC-Berkeley team fed 12 quarters of Kepler data. Petigura wanted to find out how many Earth-sized planets Kepler was missing, their faint signals lost in the ‘noise’ of a transit lightcurve. Measuring the fraction of planets Kepler wasn’t seeing, the team was able to extract 119 Earth-like worlds ranging from six times Earth’s diameter all the way down to a planet the size of Mars. Thirty-seven of the team’s planets had not been identified in the previous Kepler work.

Image: The fraction of Sun-like stars having planets of different sizes, orbiting within 1/4 of the Earth-Sun distance (0.25 AU) of the host star. The graph shows that planets as small as Earth (far left) are relatively common compared to planets 8.0x the size of Earth (similar to Jupiter). For example, 7.9% of Sun-like stars harbor a planet with a size of 1.0-1.4 times the size of Earth, orbiting inward of 1/4 the Earth-Sun distance (closer than Mercury’s distance from the Sun). There are increasing numbers of planets from 8x the size of Earth down to 2.8x Earth. Remarkably, the number of planets smaller than 2.8x Earth is approximately constant with planet size, down to the size of our Earth. The gray indicates the planets discovered in this study, and the orange represents the correction applied to account for planets the TERRA software would miss statistically, typically about 20%. Credit: Image by Erik Petigura and Geoff Marcy, UC Berkeley, and Andrew Howard, Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawaii.

This study takes us another step along the way to a major exoplanet goal. Getting a sound estimate of the fraction of Sun-like stars bearing Earth-sized planets in the habitable zone — eta Earth — is tantalizingly close, and the paper on this work points out that its 12,000 stars will be among the sample from which this estimate is drawn. The Berkeley team homes in on close-in planets as a way of studying planet frequency in relation to size, the assumption being that estimates of habitable zone ‘Earths’ will tighten as we get further data. From the paper:

Our key result is the plateau of planet occurrence for the size range 1-2.8 RE for planets having periods 5-50 days. With 8 years of total photometry in an extended Kepler mission (compared to 3 years here), the computational machinery of TERRA— including its light curve de-trending, transit search, and completeness calibration—will enable a measurement of [eta Earth] for habitable zone orbits with extended mission photometry.

All in all, the team estimates that uncertainties in detection mean that Kepler misses about one in four big Earth-sized worlds, a figure this work now corrects. Planets larger than Earth in this category may often turn out to be more like Neptune than Earth, with a rocky core surrounded by helium and hydrogen — planets like these may, in close orbits, be water worlds with vast oceans and no exposed land surface. But the UC-Berkeley work gives us plenty of reason to think that rocky worlds like Earth within stellar habitable zones are going to be anything but rare.

On Artifacts Future and Past

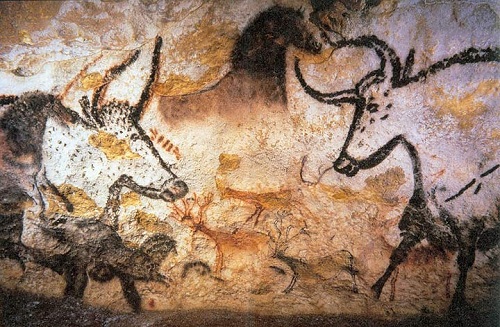

How are you affected by the cave paintings at Lascaux? The paleolithic art in this region of southwestern France dates back perhaps 18,000 years, depicting large animal figures, human forms and abstract symbols. Some believe the paintings even contain astronomical pointers — star charts — but theories on how to interpret them abound, and whatever spin we put on them, we’re confronted by the mystery of evocative imagery reaching out over centuries. Lascaux and other such sites take us beyond civilization and into the realm of deep time, a place where our parochial concerns are dwarfed by this reminder of humanity’s aggregated experience.

Early cave art reaches almost twice as far back as the 10,000 year clock proposed by Danny Hillis and the Long Now Foundation hopes to take us forward. Yet the experience of the two is in some ways similar. Building a clock designed to tell time by the year and century places our short lives in perspective and demands we take a view that encompasses our remote descendants. Long-term thinking, forward or back, is about identifying the forces shaping the human experience and asking what we can do today to influence an outcome we will never live to see.

In some ways, artifacts like the Voyager Golden Record are cousins of the cave paintings, for they collect various statements about who we are and project them into the realm of deep time. It’s equally hard to imagine what far future audience the cave painters might have had in mind, if any, and what audience the Golden Records might one day achieve. But for chance we might never have learned about Lascaux, the paintings of which were discovered by a French teenager in 1940. And what chance is there that some extraterrestrial civilization may one day recover an intact Voyager, long silent but bearing the testimony of the record that identifies its makers?

Image: One of the cave paintings of Lascaux, a chance discovery that brought the early human experience to vivid life. Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

I’m thinking about Lascaux this morning because a scene from the cave art is one of the images chosen by writer and artist Trevor Paglen for a multimedia project called The Last Pictures, an archive of 100 black and white photographic images launched into geosynchronous orbit aboard a communications satellite in November. Paglen had been contemplating the fact that most satellites in low Earth orbits eventually return to Earth, forced down by the inexorable processes of orbital decay. But communications satellites, almost 36,000 kilometers above the equator, are up there for good. “These satellites are the longest-lasting things that humans have ever made,” Paglen told The Atlantic‘s Austin Considine in a recent interview. “Very few, if any, traces of human civilization [will remain] on the surface of the earth. But a ring of dead satellites and spaceships will remain in orbit, essentially, forever.”

So Paglen set about choosing photographs that would record the human experience, working with artists, scientists, philosophers and anthropologists to decide how to encapsulate it. Drawing on the expertise of a team at MIT and weighing the physical constraints for an archive he saw as lasting several billion years, the chosen images were etched into a silicon wafer that was bolted along with its protective shell onto the EchoStar XVI, a satellite operated by Dish Network. The satellite is expected to carry programming for 15 years, the archive to survive for billions more.

Have a look at Considine’s piece, which reproduces several of the images, including art from Lascaux as well as cherry blossoms against a clear sky, a waterspout in the Florida Keys and a group of orphan refugees from Greece and Armenia wading into the sea for the first time. How you cull 100 images out of the vast possibilities in archives around the world is a story in itself, and it’s clear that Paglen had no didactic agenda in their selection. No captions accompany the satellite-born text (although they are available in an accompanying book available through Paglen’s site). Like the cave paintings, Paglen’s images are evocative without shedding obvious meaning, capable of deep layers of interpretation and conveying a sense of shared experience.

Considine’s interview is itself moody and interesting. Here’s a bit more of it:

Sagan’s records implicitly assumed we would be around for an alien follow-up call. It tried — ambitiously, if somewhat arrogantly — to make a good first impression. “The Last Pictures” assumes it is impossible to say anything universal or lasting about humanity, and that we’ll be long gone by the time its pictures are discovered, if they’re found at all.

“This is not a project that’s supposed to explain to aliens what humans are all about and be the definitive record of human civilization,” Paglen said. It is, he added, “a collection of images that explained to somebody in the future what happened to all of the people who built the dead spaceships in orbit around the earth. And how they killed themselves.” (Or perhaps were killed?)

As art, this is work that proceeds without any certainty of a future audience, and makes its statement by that very ambiguity. If our species works its way through the thousand traps of technological growth and survives, the Paglen photographs become a time capsule of the sort we tend to stick in the cornerstone of buildings, and we can imagine humans of the future looking upon the ancient satellite as no more than a curiosity. If we don’t survive, we can imagine the same faint chance the Voyagers have of being detected and studied by some other intelligence, a thought that adds an almost unbearable poignancy to some of these images.

I wouldn’t want to try to convey the experience of an entire species through any series of images, and with a number as small as 100, the choice seems hopelessly arbitrary. But what gives the work a certain fascination is that we live in an era when we can create something that could outlive its makers not just by millennia but by eons. There will be more such things as we continue to push out into the Solar System, with space probes that continue their journeys long after they have fallen silent, and all will bear witness to the civilization that put them in motion. That in itself is evocative of the deep mystery we all face as we confront our existence, a mystery the cave painters surely felt as they captured hunters, bison and aurochs on walls of ancient stone.

Planets Everywhere You Turn

Exactly what kind of planets can form around M-class dwarf stars is a major issue. After all, these stars, comprising 70 percent or more of the stars in the galaxy, are far more common than stars like the G-class Sun. About 5500 of the 160,000 stars the Kepler mission is looking at are M-dwarfs, and of these, 66 had been found to show at least one planetary transit signal at the time a new paper on M-dwarf planets was in preparation. That paper, the work of John Johnson and postdoc Jonathan Swift (Caltech) and team, homes in on the Kepler-32 system, whose five transiting planets offer a chance to study planet formation and frequency around such stars.

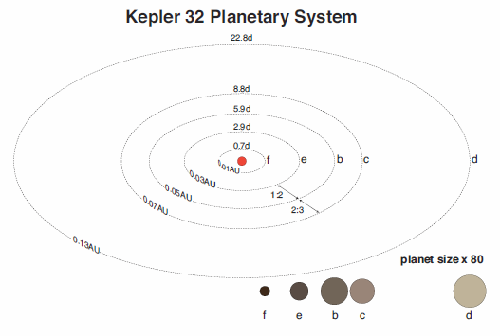

Kepler-32 is about half as massive as the Sun and has half its radius, with about 5 percent of its luminosity. The planets here have radii that range from 0.8 to 2.7 times that of the Earth, all of them orbiting within about a tenth of an astronomical unit from the star, a distance that is about a third of the radius of Mercury’s orbit around the Sun. The outermost of the five planets lies in the habitable zone. The Caltech team used Kepler data in correlation with observations from the Keck Observatory and the Palomar 60-inch telescope to characterize the system in detail. Two of the planets had already been confirmed, and the team has now confirmed the other three.

Image: — Depiction of the Kepler-32 planetary system with the star and orbits drawn to scale. The relative sizes of the planets are shown at the bottom of the figure scaled up by a factor of 80 in relation to their orbits. Credit: Jonathan Swift, John Johnson/Caltech.

Although the study is producing interesting material on planet formation, what’s capturing the bulk of press attention is the researchers’ estimate that there are at least 100 billion planets in the galaxy. It’s a conservative figure at that, because the analysis only includes planets in close orbits around M-dwarfs, leaving aside the issue of outer planets in such systems and planets orbiting other classes of star. To arrive at the figure, the team calculated the probability that an M-dwarf system would have the precise edge-on orientation we see with Kepler-32, combining that with the number of systems Kepler is able to detect. Even the conservative figure — essentially one planet for every star in the galaxy — is happy news for planet hunters, for it suggests that planets are the norm around the most common kind of stars in the Milky Way.

From the paper:

We select out 4682 M dwarfs from the Kepler Input Catalog that have been observed with Kepler and use their observational parameters to derive the planet occurrence rate of Kepler M dwarf planet candidates. We confirm that within the completeness limits of the first 6 quarters of Kepler data, the M dwarf planet candidates have an occurrence rate about 3 times that of solar-type stars, while the occurrence rate of all candidates around M dwarfs is 1.0±0.1. We expect the fidelity of our culled sample to be above 90%. Thus the compact systems of planets around the Kepler M dwarf sample are a major population of planets throughout the Galaxy amplifying the significance of the insights gleaned from Kepler-32.

The likelihood is that the five Kepler-32 planets formed much further out from the star and migrated inwards, one line of evidence being that the mass of the disk where the planets are found would be as much as three Jupiters, too much disk material for the space available based on our understanding of other proto-planetary disks. Moreover, the fact that M-dwarfs are brighter and hotter when young would have kept planet-forming dust from existing so close to the star. Yet a third line of reasoning is that the third and fourth planets of the system are not dense, implying they are composed of volatiles like carbon dioxide, methane or other ices and gases. Thus formation further out in the system with subsequent migration is the likely scenario.

The paper is Swift et al., “Characterizing the Cool KOIs IV: Kepler-32 as a prototype for the formation of compact planetary systems throughout the Galaxy,” accepted at The Astrophysical Journal (preprint).

Related: The Planetary Habitability Laboratory (University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo) notes that of the 18,406 ‘planet-like detection events’ released last month by the Kepler team, some 15,847 meet the criteria for study for possible inclusion in the institution’s Habitable Exoplanet Catalog. PHL analyzed and sorted the remaining candidates and was able to identify 262 potentially habitable worlds. These include four Mars-sized objects, 23 of Earth size, and 235 ‘super-Earths.’ The best candidate PHL sees thus far is an Earth-sized planet in a 231-day orbit around the star KIC-6210395, one that receives 70 percent of the light that Earth receives from the Sun. This interesting if preliminary analysis is reported in a news release wonderfully titled (with a nod to ‘Contact’) ‘My God, it’s full of planets! They should have sent a poet.’

Dynamics of an Interstellar Probe

Yesterday’s look at radiation and its effects on humans in space asked whether any Fermi implications were to be found in the work described at the University of Rochester. One answer is that expansion into the cosmos does not need to be biological, for biological beings can build robotic explorers equipped with enough artificial intelligence to get the job done. A truly advanced civilization would be able to create large numbers of intelligent probes or, indeed, self-replicating probes that could spread throughout the galaxy on a timescale of perhaps ten million years.

Fermi speculation is always fun but, when we get into the motivations of extraterrestrial civilizations, it leads inevitably to unfalsifiable solutions, good for conversation over coffee but incapable of producing a scientific result. Thus the ‘zoo hypothesis,’ the notion that the Earth is intentionally left alone to pursue its own development by beings with an agenda of their own. It makes for terrific science fiction, but how much can we say about alien sociology? Working with two colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, Duncan Forgan thinks we’d be better off studying the physical constraints that might govern an expanding wave of galactic exploration.

Image: The spiral galaxy NGC 4414, as imaged by the Hubble Space Telescope. Can simulations help us understand how a galaxy of hundreds of billions of stars can be explored by a single civilization? Credit: NASA.

Forgan argues that even in our early exploration of the Solar System, we’ve learned the value of gravitational ‘slingshot’ maneuvers that let us produce velocity and trajectory changes without the use of fuel. Simple powered flight is an inefficient way to travel, especially in our era of chemical rocketry and, presumably, in the coming era of nuclear propulsion methods. At the galactic level, probes can be accelerated relative to the galactic rest frame by similar techniques. Forgan and team run simulations analyzing the ways a single probe can move through a population of stars.

Specifically, the researchers work with three scenarios: 1) The ‘powered’ approach, in which a single probe simply moves between stars by targeting the nearest unvisited neighbor; 2) The ‘slingshot’ approach, using gravitational slingshot methods to move along the same course as in scenario 1; and 3) The ‘maxspeed’ approach, where a probe selects the next destination star in such a way as to get the biggest benefit from a slingshot maneuver — all this depends on the destination’s star’s velocity relative to the current star being approached. The three simulation scenarios were carried out in a field of 1 million stars at a density of 1 star per cubic parsec.

What Forgan and team are looking for is the effect of these different strategies on relative travel times, as the paper notes:

We select a relatively low maximum velocity of 3 X 10-5c, where c is the speed of light in vacuo. This is comparable to the maximum velocities obtained by unmanned terrestrial probes such as the Voyager probes. Admittedly, the Voyager probes achieved these speeds thanks to slingshot trajectories, so the top speed of human technology under purely powered flight is unclear. To some extent, the maximum powered speed of the probe is less important – increasing or decreasing this maximum will simply affect the absolute values of the resulting travel times in a similar fashion. What is more important is the relative effect of changing the propulsion method and/or the trajectory.

The slingshot trajectory turns out to have a significantly shorter travel time than either the powered or maxspeed approaches, following the same course as the ‘powered’ probe but able to boost its velocity at every stage of the journey. In fact, Forgan’s simulations show the probe will have increased its velocity by close to a factor of 100 in the course of the simulations. The ‘maxspeed’ scenario optimized for velocity but did not consider the distance to the next star, creating lengthy journeys between widely spaced stars in the early stages of the exploration.

Forgan notes that with the current speed limitations of human probes, the galaxy could not be explored with a single probe in the lifetime of the universe, but the use of multiple probes changes the picture entirely:

Given our current ability to manufacture large numbers of similar sized craft for terrestrial uses, it is not unlikely that we can adopt a similar approach to building probes. A simple calculation shows that producing 1011 Voyager-esque probes would allow humankind to explore the Galaxy in 109 years. Given that around 5 X 107 automobiles are produced each year globally, it seems reasonable to expect a coordinated global effort could produce the requisite probes within a few thousand years. If the probes are made to be self-replicating, using materials en route to synthesize copies, the exponential nature of this process cuts down exploration time dramatically.

Whatever the case — a fleet of probes created by an extraterrestrial civilization or an exponentially growing fleet of probes each engaged in self-replication — adding gravitational slingshot dynamics into the mix can shorten travel times and strengthen the Fermi paradox. Slingshot effects reduce a single probe’s travel time by two orders of magnitude. Forgan’s team is now repeating the analysis of this paper using self-replicating probes as the basis of exploring whether slingshot dynamics fit into the overall cost-benefit picture of that kind of expansion.

The paper is Forgan, Papadogiannakis and Kitching, “The Effect of Probe Dynamics on Galactic Exploration Timescales,” accepted for publication in JBIS (preprint).

Radiation, Alzheimer’s Disease and Fermi

In a sobering start to the New Year, at least for partisans of manned missions to deep space, new work out of the University of Rochester indicates that galactic cosmic radiation may accelerate the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. The study, led by the university’s Kerry O’Banion, is hardly the first time that the impact of radiation in space has been studied, with previous work aimed at cancer risks as well as cardiovascular and musculoskeletal issues. But O’Banion’s work points to radiation’s effects on biological processes in the brain, reaching striking conclusions:

“Galactic cosmic radiation poses a significant threat to future astronauts,” said O’Banion. “The possibility that radiation exposure in space may give rise to health problems such as cancer has long been recognized. However, this study shows for the first time that exposure to radiation levels equivalent to a mission to Mars could produce cognitive problems and speed up changes in the brain that are associated with Alzheimer’s disease.”

Neurological damage from human missions to deep space — and the study goes no further than the relatively close Mars — would obviously affect our planning and create serious payload constraints given the need for what might have to be massive shielding. I’m already seeing this work being referred to (not by these researchers, to be sure) in the context of the Fermi paradox, which is an interesting speculation in itself, the idea being that if space is inherently hostile to human biology, these conditions may have prevented other species from tackling interstellar journeys. But before we get into that, let’s take a closer look at how the study was put together.

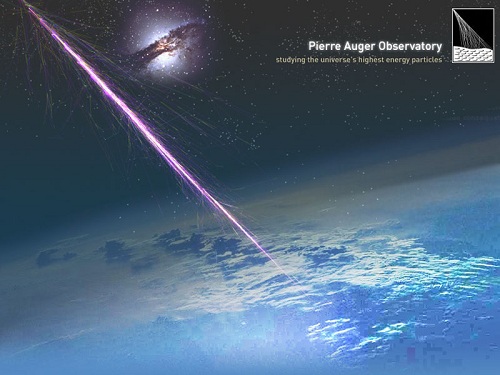

Image: An artist’s illustration of a cosmic ray striking the Earth’s atmosphere and creating a shower of secondary particles detectable on the surface. That high energy fundamental particles are barreling through the universe has been known for about a century. Because ultra high energy cosmic rays are so rare and because their extrapolated directions are so imprecise, no progenitor objects have ever been unambiguously implied. 2007 results from the Pierre Auger Observatory, however, indicate that 12 of 15 ultra high energy cosmic rays have sky directions statistically consistent with the positions of nearby active galactic nuclei. Whatever the source, does such space radiation present a show-stopper for manned missions to deep space? Credit: Robert Nemiroff & Jerry Bonnell / Pierre Auger Observatory Team.

At the heart of the work are high-energy, high-charged particles (HZE) which exist in low but continuous levels in deep space. Among the different HZE particles, the focus of the O’Banion team’s work is 56Fe — iron particles — which are speedy and massive enough to create serious shielding problems. To examine the issue, O’Banion exposed laboratory mice to doses of radiation comparable to what astronauts would experience on a trip to Mars, working partly at NASA’s Space Radiation Laboratory at Brookhaven National Laboratory (Long Island).

The mice were then put through a variety of experiments to gauge the cognitive and biological effect of the exposure. The result: Their encounter with radiation resulted in what the paper calls ‘enhanced AD [Alzheimer’s disease] plaque pathology,” with higher than normal accumulations of beta amyloid, the protein plaque now considered a marker for the disease. From the paper (internal references omitted for brevity):

The doses used in this study are comparable to those astronauts will see on a mission to Mars, raising concerns about a heightened chance of debilitating dementia occurring long after the mission is over. Increased plaque progression could be due to a variety of mechanisms. A primary mechanism of radiation injury is DNA damage and reactive oxygen species production that can contribute to overall cell dysfunction. In addition, radiation is also known to cause glial activation and inflammatory cytokine production, both of which have been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases like AD. In our study, GCR exposure could amplify the chronic inflammatory AD state and speed up pathology.

The mice were also run through experiments involving recall of objects and locations, with the researchers finding that the group exposed to radiation was far more likely to fail at these tasks, suggesting an earlier onset of neurological impairment than normal. The paper stresses this caveat: The mice were exposed to a single kind of galactic cosmic radiation at acute levels of exposure. “It is not known how the CNS [central nervous system] will respond to the complex and chronic low-dose GCR environment of space. Moreover, astronauts will not likely be familial AD carriers. Therefore, while many of the pathological processes are believed to be similar, this model does not reflect the complete human condition.”

So the model is tightly focused, but the one aspect of deep space radiation the researchers can replicate is troubling. Whole body exposure to 56Fe particle HZE radiation appears to enhance the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. You can read more about this work in this University of Rochester news release. The paper itself is Cherry et al., “Galactic Cosmic Radiation Leads to Cognitive Impairment and Increased A? Plaque Accumulation in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease,” PLoS ONE 7(12): e53275 (available online).

Back briefly to the Fermi issue, which in my judgment remains unaffected by the question of radiation danger. We do not need to assume that a wave of interstellar probes, whether self-replicating or not, would have to be manned by biological creatures. In fact, assuming they’re not, we can stop worrying about mission times of a human life-span or less and think about a galaxy penetrated by artificial intelligence gradually moving from star to star, perhaps leaving observation stations along the way. Given enough time, the galaxy would be infused with the technology of a single species which would never need to expose itself to deep space.