Centauri Dreams

Imagining and Planning Interstellar Exploration

Mixing and Growth in the Sun’s Protoplanetary Disk

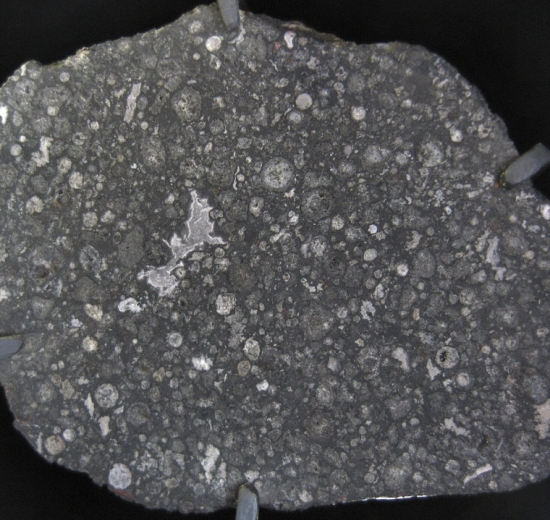

The Allende meteorite is the largest carbonaceous chondrite meteorite ever discovered. Falling over Mexico’s state of Chihuahua in 1969 and breaking up in the atmosphere, the object yielded over two tons of material that have provided fodder for scientists interested in the early days of the Solar System. The meteorite contains numerous calcium-aluminum-rich inclusions (CAIs), which are considered to be the first kind of solids formed in the system 4.5 billion years ago.

Samples of the Allende meteorite are considered ‘primitive,’ which in this parlance means unaffected by significant alteration since formation. Now a team led by Tom Zega (University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory) has gone to work on a dust grain from this object, in order to simulate the conditions under which it formed in the Sun’s protoplanetary disk. The grain was drawn from one of several CAIs discovered in the Allende meteorite sample. Analysis of the sample’s chemistry and crystal structure provides a look at the conditions that produced it.

The work appears in The Planetary Science Journal and is, according to Zega, something of a ground-breaker:

“As far as we know, our paper is the first to tell an origin story that offers clues about the likely processes that happened at the scale of astronomical distances with what we see in our sample at the scale of atomic distances.”

Image: A slice through an Allende meteorite reveals various spherical particles, known as chondrules. The irregularly shaped “island” left of the center is a calcium-aluminum rich inclusion, or CAI. The grain in this study was isolated from such a CAI. Credit: Shiny Things/Wikimedia Commons.

To examine the CAI, the researchers used a scanning transmission electron microscope located at the University of Arizona as well as a twin instrument at the Hitachi factory in Hitachinaka, Japan. The microstructure of the sample was examined at varying scales down to the level of individual atoms, in a process co-author Venkat Manga (UA) likens to opening a book recording what happened 4.567 billion years ago in the nebula that gave birth to the Sun.

It’s a book with an intriguing plot. The investigation revealed types of minerals called spinel and perovskite. Examined at the level of atomic-scale crystal structure, the sample creates a puzzle, with Zega noting that the chemical pathways that produced it seem to contradict current theories on the processes at work in protoplanetary disks. I like the way Zega puts this: “Nature is our lab beaker, and that experiment took place billions of years before we existed, in a completely alien environment.”

The paper recounts the team’s effort to create new formation models that could produce the sample CAIs found in the Allende object, simulating their chemistry and cutting across the fields of materials and mineral science as well as microscopy in the kind of multidisciplinary challenge that the study of planetary systems involves. Just how wide-ranging such work can be is made clear in the paper:

Our motivation is to understand the micro- and atomic-scale structure of the materials reported herein, which defy existing thermochemical models of the early solar protoplanetary disk. To this end, we combine state-of-the-art nanoscale to atomic-scale characterization of several CAIs with quantum-mechanical, thermodynamic modeling and dust-transport calculations to explain their origin. We propose that such an integrated approach is an important step toward a more comprehensive paradigm for reverse engineering the microstructures observed within primitive meteorites and extracting from them the thermal and dynamic histories that they have recorded.

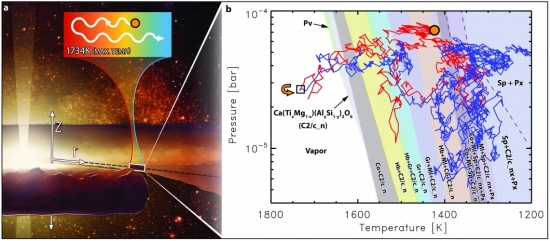

The history of the particle at the heart of the model is worked out in detail, showing us a dynamic journey moving from a region of the disk near Earth’s current orbit to close proximity to the Sun and later transport to cooler regions further out. The sample winds up being part of an asteroid which, as it fragmented, became the parent body of meteorites like the Allende object. Crucial here is the history of movement and mixing within the disk, which challenges earlier, more static models.

It is clear from the above observations and computational effort that some assemblages within the oldest solar system solids deviate from long-standing assumptions and, rather than remaining in contact with the same parcel of gas in a monotonically cooling system, are admixed into other regions, possibly warming once or multiple times before cooling down in the disk. Indeed, this mixing and transport are necessary for the preservation of CAIs for millions of years and the delivery of CAI-like grains to outer regions of the solar nebula to be accreted by comets as revealed by the Stardust mission (Brownlee et al. 2006).

Image: Illustration of the dynamic history that the modeled particle could have experienced during the formation of the solar system. Analyzing the particle’s micro- and atomic-scale structures and combining them with new models that simulated complex chemical processes in the disk revealed its possible journey over the course of many orbits around the sun (callout box and diagram on the right). Originating not far from where Earth would form, the grain was transported into the inner, hotter regions, and eventually washed up in cooler regions. Credit: Heather Roper/Zega et al.

The authors say that their work is part of a longer-term effort to “deconstruct CAIs phase by phase,” so we should be hearing more about these methods. It will be interesting to see how asteroid sample return missions provide further insights.

We are digging here into the nature of planet formation as we try to understand how material moves around inside a protoplanetary disk. These are presumably processes common to the emerging systems we also see with the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), whose images show the earliest stages of stellar system growth. But examining that commonality with a critical eye will be part of the continuing study of evolving disks and the movement of materials within them.

The paper is Zega et al., “Atomic-scale Evidence for Open-system Thermodynamics in the Early Solar Nebula,” Planetary Science Journal Vol. 2, No. 3 (17 June 2021). Full text.

Email Subscribers Take Note

Google will no longer be supporting its email distribution service as of July 1, and I am preparing for this through the work of my friend Frank Taylor, who is fine-tuning a replacement. However, I’ve had a few reports already of emails not being delivered. So if you are an email subscriber to Centauri Dreams, please bear with us as Frank gets the new service up and running. This may take a few more days. There will be no need to re-subscribe, as the existing subscription list will be transferred to the new feed.

An AI Toolbox for Space Research

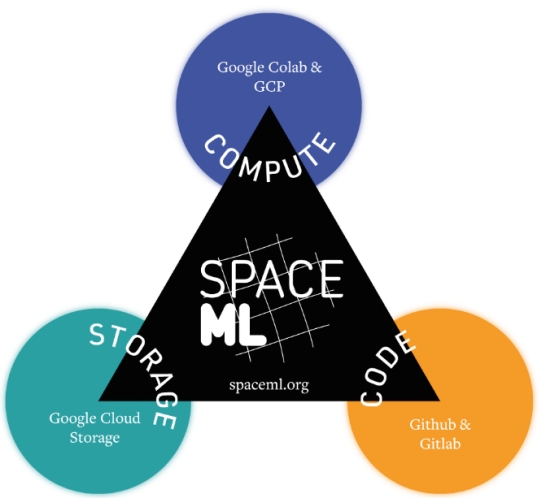

Let’s take a brief break from research results and observational approaches to consider the broader context of how we do space science. In particular, what can we do to cut across barriers between different disciplines as well as widely differing venues? Working on a highly directed commercial product is a different process than doing academic research within the confines of a publicly supported research lab. And then there is the question of how to incorporate ever more vigorous citizen science.

SpaceML is an online toolbox that tackles these issues with a specific intention of improving the artificial intelligence that drives modern projects, with the aim of boosting interdisciplinary work. The project’s website speaks of “building the Machine Learning (ML) infrastructure needed to streamline and super-charge the intelligent applications, automation and robotics needed to explore deep space and better manage our planetary spaceship.”

I’m interested in the model developing here, which makes useful connections. Both ESA and NASA have taken an active interest in enhancing interdisciplinary research via accessible data and new AI technologies, as a recent presentation on SpaceML notes:

NASA Science Mission Directorate has declared [1] a commitment to open science, with an emphasis on continual monitoring and updating of deployed systems, improved engagement of the scientific community with citizen scientists, and data access to the wider research community for robust validation of published research results.

Within this context, SpaceML is being developed in the US by the Frontier Development Lab and hosted by the SETI Institute in California, while the UK presence is via FDL at Oxford University and works in partnership with the European Space Agency. This is a public-private collaboration that melds data storage, code-sharing and data analysis in the cloud. The site includes analysis-ready datasets, space science projects and tools.

Bill Diamond, CEO of the SETI Institute, explains the emergence of the approach:

“The most impactful and useful applications of AI and machine learning techniques require datasets that have been properly prepared, organized and structured for such approaches. Five years of FDL research across a wide range of science domains has enabled the establishment of a number of analysis-ready datasets that we are delighted to now make available to the broader research community.”

The SpaceML.org website includes a number of projects including the calibration of space-based instruments in heliophysics studies, the automation of meteor surveillance platforms in the CAMS network (Cameras for Allsky Meteor Surveillance), and one of particular relevance to Centauri Dreams readers, a project called INARA, which stands for Intelligent ExoplaNET Atmospheric RetrievAl. Its description:

“…a pipeline for atmospheric retrieval based on a synthesized dataset of three million planetary spectra, to detect evidence of possible biological activity in exoplanet atmospheres.”

SpaceML will curate a central repository of project notebooks and datasets generated by projects like these, with introductory material and sample data allowing users to experiment with small amounts of data before plunging into the entire dataset. New datasets growing out of ongoing research will be made available as they emerge.

I think researchers of all stripes are going to find this approach useful as it should boost dialogue among the various sectors in which scientists engage. I mentioned citizen scientists earlier, but the gap between academic research labs, which aim at generating long-term results, and industry laboratories driven by the need to develop commercial products to pay for investment is just as wide. Availability of data and access to experts across a multidisciplinary range creates a promising model.

James Parr is FDL Director and CEO at Trillium Technologies, which runs both the US and the European branches of Frontier Development Lab. Says Parr:

“We were concerned on how to make our AI research more reproducible. We realized that the best way to do this was to make the data easily accessible, but also that we needed to simplify both the on-boarding process, initial experimentation and workflow adaptation process. The problem with AI reproducibility isn’t necessarily, ‘not invented here’ – it’s more, ‘not enough time to even try’. We figured if we could share analysis ready data, enable rapid server-side experimentation and good version control, it would be the best thing to help make these tools get picked up by the community for the benefit of all.”

So SpaceML is an AI accelerator, one distributing open-source data and embracing an open model for the deployment of AI-enhanced space research. The current datasets and projects grow out of five years of applying AI to space topics ranging from lunar exploration to astrobiology, completed by FDL teams working in multidisciplinary areas in partnership with NASA and ESA and commercial partners. The growth of international accelerators could quicken the pace of multidisciplinary research.

What other multidisciplinary efforts will emerge as we streamline our networks? It’s a space I’ll continue to track. For more on SpaceML, a short description can be found in Koul et al., “SpaceML: Distributed Open-source Research with Citizen Scientists for the Advancement of Space Technology for NASA,” COSPAR 2021 Workshop on Cloud Computing for Space Sciences” (preprint).

Finding the Missing Link: How We Could Discover Interstellar Quantum Communications

Six decades of SETI have yet to produce a detection. Are there strategies we have missed? In today’s essay, Michael Hippke takes us into the realm of quantum communication, explaining how phenomena like ‘squeezed light’ can flag an artificial signal with no ambiguity. Quantum coherence, he argues, can be maintained over interstellar distances, and quantum methods offer advantages in efficiency and security that are compelling. Moreover, techniques exist with commercially available equipment to search for such communications. Hippke is a familiar face on Centauri Dreams, having explored topics from the unusual dimming of Boyajian’s Star to the detection of exomoons using what is known as the orbital sampling effect. He is best known for his Transit Least Squares (TLS) exoplanet detection method, which is now in wide use and has accounted for the discovery of ~ 100 new worlds. An astrophysics researcher at Sonneberg Observatory and visiting scholar for Breakthrough Listen at UC-Berkeley, Michael now introduces Quantum SETI.

by Michael Hippke

Almost all of today’s searches for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI) are focused on radio waves. It would be possible to extend our search to include interstellar quantum communications.

Quite possibly, our Neanderthal ancestors around the bonfires of the Stone Age marveled at the night sky and scratched their heads. What are all these stars about? Are there other worlds out there which have equally delicious woolly mammoths? Much later, about 200 years ago, the great mathematician Carl Friedrich Gauß proposed to cut down large areas of Siberian forest, in the form of a triangle, to send a message to the inhabitants of the Moon. At the end of the 19th Century, many canals were built, including the Suez and Panama canals. Inspired by these engineering masterpieces, astronomers searched for similar signs of technology on other planets. The logic was clear: What the great human civilization can build must reflect what other civilizations will inevitably build.

Clearly, Martians must equally be in need of canals. Indeed, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli discovered “canali” on Mars in 1877. Other observers joined the effort, and Percival Lowell asserted that the canals exist and must be artificial in origin.

Something similar happened again a short time later when Guglielmo Marconi put the first radio into operation in December 1894. Just a few years later, Nikola Tesla searched for radio waves from Mars, and believed he had made a detection. It turned out to be a mistake, but the search for radio signals from space continued. The “Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence,” or SETI for short, received a boost in 1960 from two publications in the prestigious journal Nature. For the first time, precise scientific descriptions were given for the frequencies and limits of interstellar communication using radio waves [https://www.nature.com/articles/184844a0] and optical light [https://www.nature.com/articles/190205a0]. Between 1960 and 2018, the SETI Institute recorded at least 104 experiments with radio telescopes [https://technosearch.seti.org/]. All unsuccessful so far, which is also true for searches in the optical domain, for X-rays, or infrared signatures.

Photons? Neutrinos? Higgs bosons?

Particle physics radically changed our view of the world in the 20th century: It was only through the understanding of elementary particles that discoveries such as nuclear fission (atomic weapons, nuclear power plants) became possible. Of the 37 elementary particles known today in the Standard Model, several are suitable for an interstellar communication link. I examined the pros and cons of all relevant particles in a 2018 research paper [https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.07962]. The known photons (light particles) were the “winners”, because they are massless and therefore energetically favorable. In addition, they travel at light speed, can be focused very well, and can carry several bits of information per particle.

Photons are not only known as light particles – they are also present in the electromagnetic spectrum as radio waves, and with higher particle energies than X-rays or gamma rays. In addition, there are other particles that can be more or less reasonably used for communication. For example, it has been demonstrated that neutrinos can be used to transmit data [https://arxiv.org/abs/1203.2847]. Neutrinos have the advantage that they effortlessly penetrate kilometer-thick rock. However, this is also one of their disadvantages: they are extremely difficult to detect, because they also penetrate (almost) every detector.

Incidentally, the particle that is the least suitable of all for long-distance communication is the Higgs boson. It was predicted by Peter Higgs in 1964, but was not observed for the first time until 2012 at the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN – it also won a Nobel Prize.

The Higgs boson decays after only 10-22 seconds. To keep it alive long enough to travel to the next star, it would have to be accelerated very strongly. Due to the Lorentz factor, its subjective time would then pass more slowly. In practice, however, this is impossible to achieve, because one would have to pump so much energy into the Higgs particle that it would become a black hole. It thus disqualifies itself as a data carrier.

Photons and quanta

Quanta, simply put, are discrete particles in a system that all have the same energy. For example, in 1905 Albert Einstein postulated that particles of light (photons) always have multiples of a smallest amount of energy. This gives rise to the field of quantum mechanics, which describes effects at the smallest level. The transition to the macroscopic, classical world is a grey area – quantum effects have also been demonstrated in fullerenes, which are spheres of 60 carbon atoms. So although quantum effects occur in all particles, it makes sense to focus on photons for interstellar communication because they are superior to other particles for this purpose.

Four advantages of quantum communication

1. Information efficiency

Classical communication with photons, over interstellar distances, can be well illustrated in the particle model. The transmitter generates a pulse of particles, and focuses them through a parabolic mirror into a beam whose minimum diameter is limited by diffraction. This means that the light beam expands over large distances.

For example, if an optical laser beam is focused through a telescope measuring one meter and sent across the 4 light years to Alpha Centauri, the light cone there is already as wide as the distance from the Earth to the Sun. So a receiver on a planet around Alpha Centauri receives only a small fraction of the emitted photons. The rest flies past the receiver into the depths of space. On the other hand, photons are quite cheap to buy: You already get about 1019 photons from a laser that shines with one watt for one second.

In the sum of these effects, every photon is precious in interstellar communication. Therefore, one wants to encode as many bits of information as possible into each transmitted photon. How to do that?

Photons (without directional information) have three degrees of freedom: their arrival time, their energy (= wavelength or frequency), and the polarization. Based on this, an alphabet can be agreed upon, so that, for example, a photon arriving at time 11:37 with wavelength 650 nm (“red”) and polarization “left” corresponds to the letter “A”. The number of bits, which can be encoded per degree of freedom, scales unfortunately only logarithmically: 1024 modes result in 10 bits per photon. In practice, one still has to take losses and noise into account, so that with this classical communication it is rarely possible to transmit more than on the order of 10 bits per photon.

Quantum communication, however, offers the possibility to increase the information density. There are several ways to realize this, but a good illustration is based on the fact that one can “squeeze” light (more on this later). Then, for example, the time of arrival can be measured more accurately (at the expense of other parameters). There are analytical models, and also already practical demonstrations, which show that the information content can be increased by up to 50 percent. In our simple example, about 15 bits per photon could be encoded instead of only 10 for the classical case.

2. Information security

Encryption of sensitive data during data transmission is an important issue for us humans. Of course, we don’t know if this is the case for other civilizations. But it is plausible that future colonies on Mars (or Alpha Centauri…) will also want to encrypt their communications with each other and with Earth. In this respect, encryption is quite relevant for transmissions through space.

Today’s encryption methods are mostly based on mathematical one-way functions. For example, it is easy to multiply two large numbers. However, if the secret key is missing, you have to go the other way around and calculate the two prime factors from the large number. This is much more difficult. However, the security of this and similar methods is “only” due to the fact that no one has yet found an effective method of calculation. We have in no case the mathematical proof available that such a calculation is not possible. There is always the danger that a clever algorithm will be found which cracks the encryption. Quantum computers could also be used in the future to attack some encryption methods.

In contrast, there is quantum cryptography. The best-known method uses a quantum key exchange, which has also been used in practice over long distances, for example via satellite. This is based on quantum mechanics and is unbreakable as long as no mistake is made during transmission – and as long as no one disproves quantum mechanics.

3. Gate-keeping

If there really is a galactic Internet, how to protect it from being spammed by uneducated civilizations? This problem has already occupied Mieczys?aw Subotowicz, a Polish professor of astrophysics, who wrote in a technical paper on neutrino communication in 1979 that it was: “so difficult that an advanced civilization could intentionally communicate only through it with aliens of its own level of development”.

Now, as mentioned above, neutrino communications are very inefficient. It would be much more elegant and energy efficient to use photons instead. As an entry barrier, it seems plausible not to allow classical photons, but to require quantum communications. This would leave out young technological civilizations like ours, though we would have a good chance of joining in the next few decades.

4. Quantum computing

Konrad Zuse built the Zuse Z3, the first Turing-complete computer, in his Berlin apartment in 1941. This was a single computing machine. It took several decades until the first computers were connected (networked together) in 1969 with the ARPANET. This gave rise to the Internet, in which billions of computers of all kinds are connected today: PCs, cell phones, washing machines, etc. All these devices are classical computers exchanging classical information (bits) on classical paths (for example via photons in optical fibers).

In the future, quantum computers may gain importance because they can solve a certain class of problems much more efficiently. This could give rise to a “quantum Internet” in which quantum computers exchange “qubits,” or entangled quantum bits. These could be intermediate results of simulations, or even observational data that are later superimposed on each other [https://arxiv.org/abs/2103.07590].

Likewise, it is conceivable that quantum-based observational data and intermediate results will be exchanged over larger distances. This is when interstellar quantum communication comes into play. If distant civilizations also use quantum computers, their communications will consist of entangled particles.

Excursus: The (im)possible magic Pandora quantum box

The idea of using quantum entanglement to transmit information instantaneously (without loss of time) over long distances is a frequent motif in science fiction literature. For example, in the famous novel The Three Body Problem by Chinese author Liu Cixin, the “Trisolarans” use quantum entangled protons to communicate instantaneously.

This method sounds too good to be true – and unfortunately it actually contains three fundamental flaws. The first is the impossibility of exchanging information faster than the speed of light. If that were possible, there would be a causality violation: one could transmit the information before an event happens, thus causing paradoxes (“grandfather paradox” [https://arxiv.org/abs/1505.07489]). Second, quantum entanglement does not work this way: one cannot change one of two entangled particles, thereby causing an influence on the state of the partner. As soon as one of the particles is changed, this process destroys the entanglement (“no communication theorem”).

Third, an information transfer without particles (no particle flies from A to B) is impossible. Information is always bound to mass (or energy) in our universe, and does not exist detached from it. There are still open questions here, for example when and how information that flew in with matter comes out of a black hole again. But this does not change the fact that the communication by quantum entanglement, and without particle exchange, is impossible.

But wait a minute – before we throw away the “magic box of the entangled photons”, we should once more examine the idea. For there is, despite all the nonsense that is written about it, an actually sensible and physically undisputed possibility of use: known under the term “pre-shared entanglement” [https://arxiv.org/abs/quant-ph/0106052].

To perform this operation, we must first assume that we can entangle and store a large number of photons. This is not so easy: the current world record for a quantum memory preserves entanglement for only six hours. And even that requires considerable effort: It uses a ground-state hyperfine transition of europium ion dopants in yttrium orthosilicate using optically detected nuclear magnetic resonance techniques [https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14025]. But it is conceivable that technological advances will make longer storage possible. Conditions are particularly good for interstellar travel, because space is dark and cold, which slows decoherence caused by particle interactions.

So let’s assume such a quantum memory is available – what do we do with it? We take one half of the magic box on board a spaceship! And the counterpart remains on earth. Now the spaceship flies far away, and wants to communicate home. The trick is then not to send the bits of the information transmission simply on a photon letter to the earth, but to superpose each classical signal photon first with one (or more) stored entangled photons. The result is one classical photon per superposition, which is then sent “totally normally” to the receiver (for example the earth). Upon arrival, the receivers opens their own magic box and bring their part of the entangled particles with it to superposition. This allows the original message to be reconstructed.

The advantage of this procedure is increased information content: The amount of information (in bits per photon) increases by the factor log2(M), where M is the ratio of the entangled to the signal photons. Even a very large magic box is therefore of limited use, because unfortunately log2(1024), for example, is only 10. Losses and interference (due to noise, for example) also have a negative effect on the amount of encodable information. Nevertheless, “pre-shared entanglement” is a method that can be considered, because it is physically accepted – in contrast to most other ideas in popular literature.

Quantum communication in practice

But what does quantum communication look like in practice? Is there even a light source for it on earth? Yes, for a few years now this has actually been the case! When gravitational waves from merging black holes were detected for the first time at the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) in 2016, “squeezed light” was used. This is laser light traveling through a very precisely controlled crystal (an “OPO” for “Optical Parametric Oscillator”). This converts one green photon into two entangled red photons, to what is called a squeezed vacuum. This reduces phase uncertainty at the expense of amplitude fluctuation. And it is the former that matters: One would like to measure the arrival time of the photons very precisely in order to compare the length of the path with and without gravitational waves. The brightness of the photons is not important.

Such a squeezed light, with lower fluctuations compared to classical light, also improves interstellar communication. It still remains unresolved what is the best way to modulate the actual data. Signal strength is also still low, with just a few watts of squeezed light in use at LIGO. By comparison, there are classical lasers in the megawatt range. So the development of quantum light is several decades behind classical light. But more powerful quantum light sources in the kilowatt range are already planned for next-generation gravitational wave detectors. This would also mark the entry threshold for meaningful interstellar quantum communications.

Detection of quantum communication

Entangled photons are also just photons – shouldn’t they already be detectable in optical SETI experiments anyway? In principle this is correct, because for a single photon it is in principle not determinable who or what has generated it. If it falls on the detector at 11:37 a.m. with a wavelength of 650 nm (color red), we cannot possibly say whether it came from a star or from the laser cannon of the Death Star.

However, a photon rarely comes alone. If we receive one thousand photons with 650 nm within one nanosecond from the direction of Alpha Centauri in our one-meter mirror telescope, then we can be sure that they do not come from the star itself (the star sends only about 32 photons of all wavelengths per nanosecond into our telescope). Classical optical SETI is based on this search assumption. It is thus very sensitive to strong laser pulses, but also very insensitive to broadband sources.

Quantum SETI extends the search horizon by additional features. If we receive a group of photons, they no longer have to correspond to a specific wavelength, or arrive in a narrow time interval, for us to assume an artificial origin. Instead, we can check for quantum properties, such as the presence (or absence) of squeezed light. Indeed, there is no (known) natural process that produces squeezed light. If we receive such, it would be extremely interesting in any case. And there are indeed tests for squeezed light that can be done with existing telescopes and detectors. In the simplest case, one tests the intensity and its variance for a nonlinear (squared) correlation, which requires only a good CCD sensor [https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevLett.125.113602].

There are numerous other tests for quantum properties of light that are applicable to starlight. For faint sources from which only a few photons are received, one can measure their temporal separation. Chaotic starlight is temporally clustered, so it is very likely to reach us in small groups. Classical coherent light, i.e. laser light, is much more uniform. For light with photon “antibunching”, in the extreme case, the distance between every two photons is identical – so their arrival times are perfectly uncorrelated. This quantum mechanical effect can never occur in natural light sources, and is thus a sure sign of a technical origin. The technique is used from time to time because it is useful for determining stellar diameters (“intensity interferometry”).

For a few stars we can already deduce on the basis of existing data that they are of natural origin: Arcturus, Procyon and Pollux [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/472/4/4126/4344853]. In the future, however, the method can be applied to a large number of “strange” objects to test them for an artificial origin: impossible triple stars [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/445/1/309/988488], hyperfast globular clusters [https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2041-8205/787/1/L11], or generally all interesting objects listed in the “Exotica” catalog by Brian Lacki (Breakthrough Listen) [https://arxiv.org/abs/2006.11304].

Current status and outlook

The idea to extend SETI by quantum effects is still quite new. However, one can fall back on known search procedures and must adapt these only slightly. Thus, dubious light sources can be effectively checked for an artificial origin in the future. We can be curious what the next observations will show, and ask the question: “Dear photon, are you artificially produced?”

The paper is Hippke, “Searching for interstellar quantum communications,” in press at the Astronomical Journal (preprint). See also the video “Searching for Interstellar Quantum Communications,” available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kwue4L8m2Vs.

Mapping the Boundary of the Heliosphere

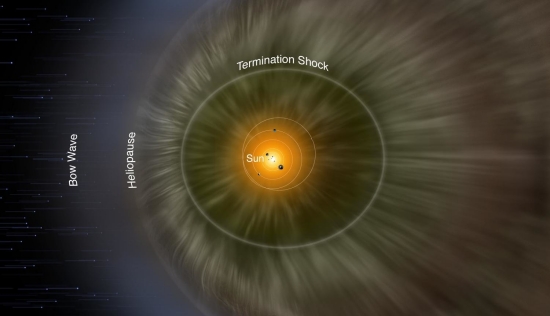

Between the Solar System and interstellar space is a boundary layer called the heliosheath. Or maybe I should define this boundary as being between the inner, planetary part of the Solar System and interstellar space. After all, we consider the Oort Cloud as part of our own system, yet it begins much further out. Both Voyagers have crossed the region where the Sun’s heliosphere ends and interstellar space begins, while they won’t reach the Oort, by some estimates, for another 300 years.

The broader region is called the heliopause, a place where the outflowing solar wind of protons, electrons and alpha particles (two protons and two neutrons tightly bound) encounters what we can call the interstellar wind, itself pushing up against the heliosphere and confining the solar wind-dominated region to a bubble. We now learn that this boundary region has been mapped, showing interactions at the interface.

A paper describing this feat has now appeared, with Dan Reisenfeld (Los Alamos National Laboratory) as lead author. Says Reisenfeld:

“Physics models have theorized this boundary for years. But this is the first time we’ve actually been able to measure it and make a three-dimensional map of it.”

Image: A diagram of our heliosphere. For the first time, scientists have mapped the heliopause, which is the boundary between the heliosphere (brown) and interstellar space (dark blue). Credit: NASA/IBEX/Adler Planetarium.

Riesenfeld and team used data from IBEX, the Interstellar Boundary Explorer satellite, which orbits the Earth but detects energetic neutral atoms (ENAs) from the zone where solar wind particles collide with those of the interstellar wind. Reisenfeld likens the process to bats using sonar, with IBEX using the solar wind as the outgoing signal and mapping the return signal, which varies depending on the intensity of the solar wind striking the heliosheath. Changes in the ENA count trigger the IBEX detectors.

“The solar wind ‘signal’ sent out by the Sun varies in strength, forming a unique pattern,” adds Reisenfeld. “IBEX will see that same pattern in the returning ENA signal, two to six years later, depending on ENA energy and the direction IBEX is looking through the heliosphere. This time difference is how we found the distance to the ENA-source region in a particular direction.”

The IBEX data cover a complete solar cycle from 2009 through 2019. We learn that the minimum distance from the Sun to the heliopause is about 120 AU in the direction facing the interstellar wind, while in the opposite direction, we see a tail that extends to at least 350 AU, which the paper notes is the distance limit of the measurement technique. The asymmetric shape is striking. From the paper’s abstract:

As each point in the sky is sampled once every 6 months, this gives us a time series of 22 points macropixel-1 on which to time-correlate. Consistent with prior studies and heliospheric models, we find that the shortest distance to the heliopause, dHP, is slightly south of the nose direction (dHP ~ 110-120 au), with a flaring toward the flanks and poles (dHP ~ 160-180 au).

Animation: The first three-dimensional map of the boundary between our solar system and interstellar space—a region known as the heliopause. Credit: Reisenfeld et al

The data make it clear that interactions between the solar wind and the interstellar medium occur over distances much larger than the size of the Solar System. It’s also clear that because the solar wind is not steady, the shape of the heliosphere is ever changing. A ‘gust’ of solar wind causes the heliosphere to inflate, with surges of neutral particles along its outer boundary, while lower levels of solar wind cause a contraction that is detected as a concurrent diminution in the number of neutral particles.

IBEX has been a remarkably successful mission, with a whole solar cycle of observations now under its belt. As we assimilate its data, we can look forward to IMAP — the Interstellar Mapping and Acceleration Probe, which is scheduled to launch in late 2024 and should enable scientists to extend the solid work IBEX has begun.

The paper is Reisenfeld et al., “A Three-dimensional Map of the Heliosphere from IBEX,” Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series Vol. 254, No. 2 (2021) Abstract. The paper is part of a trio of contributions entitled A Full Solar Cycle of Interstellar Boundary Explorer (IBEX) Observations, available here.

Brown Dwarfs & Rogue Planets as JWST Targets

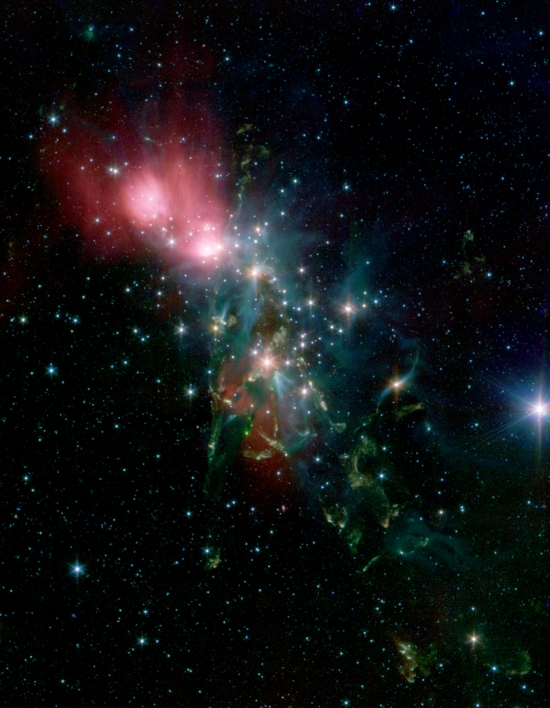

About 1,000 light years away in the constellation Perseus, the stellar nursery designated NGC 1333 is emerging as a priority target for astronomers planning to use the James Webb Space Telescope. Brown dwarfs come into play in the planned work, as do the free-floating ‘rogue’ planets we discussed recently. For NGC 1333 is a compact, relatively nearby target, positioned at the edge of a star-forming molecular cloud. It’s packed with hundreds of young stars, many of them hidden from view by dust, a venue in which to observe star formation in action.

Hoping to learn more about very low mass objects, Aleks Scholz (University of St Andrews, UK) lays out plans for using JWST to chart the distinctions between objects that emerge out of gravitational collapse of gas and dust clouds, and objects that grow through accretion inside a circumstellar disk. Says Scholz:

“The least massive brown dwarfs identified so far are only five to 10 times heftier than the planet Jupiter. We don’t yet know whether even lower mass objects form in stellar nurseries. With Webb, we expect to identify cluster members as puny as Jupiter for the first time ever. Their numbers relative to heftier brown dwarfs and stars will shed light on their origins and also give us important clues about the star formation process more broadly.”

Image: Scientists will use Webb to search the nearby stellar nursery NGC 1333 for its smallest, faintest residents. It is an ideal place to look for very dim, free-floating objects, including those with planetary masses. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. A. Gutermuth (Harvard-Smithsonian CfA).

Flying aboard JWST is an instrument called the Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS), which Scholz and colleagues will use to analyze the temperature and composition of low-mass objects like these. It is the absorption signature of a particular object, especially water and methane molecules, that will be critical for the work. The advantage of the NIRISS instrument is that it can provide simultaneous spectrographic data on dozens of objects, shortening and simplifying the observational task. One of Scholz’ team, Ray Jayawardhana (Cornell University) has been involved in JWST instrumentation since 2004, and was active in the design and development of NIRISS.

Unable to sustain hydrogen fusion, a brown dwarf may have a mass between 1% and 8% that of the Sun. Most light emitted by these objects is in the infrared, and the already tricky targets are at the top of the size range in this study. Investigating free-floating planets takes us to another level, and even with that in mind, the distinction between a brown dwarf and a giant planet can be blurry. Koraljka Muzic (University of Lisbon), also on Scholz’ team, explains:

“There are some objects with masses below the 10-Jupiter mark freely floating through the cluster. As they don’t orbit any particular star, we may call them brown dwarfs, or planetary-mass objects, since we don’t know better. On the other hand, some massive giant planets may have fusion reactions. And some brown dwarfs may form in a disk.”

Looking through Scholz’ publication list, I noticed a recent paper (“Size and structures of disks around very low mass stars in the Taurus star-forming region” — citation below) that notes the challenge to planet formation models posed by the structure of disks around such stars.

In particular, several giant planets have been found around brown dwarfs, leaving open the question of whether they formed as binary companions or as planets. If the latter, models of planetesimal accretion are hard pressed to explain the process in this environment. The movement of dust presents a problem:

Different physical processes lead to collisions of particles and their potential growth, such as Brownian motion, turbulence, dust settling, and radial drift… All of these processes have a direct or indirect dependency on the properties of the hosting star, such as the temperature and mass. For instance, from theoretical calculations, settling and radial drift are expected to be more efficient in disks around VLMS [Very Low Mass Stars] and BDs [Brown Dwarfs], with BD disks being 15-20% flatter and with radial drift velocities being twice as high or even more in these disks compared to T-Tauri disks…. With radial drift being a more pronounced problem in disks around BDs and VLMS, it is still unknown how this barrier of planet formation is overcome in these environments where the disks are more compact, colder, and have a lower mass.

The paper on the Taurus star-forming region draws on data from ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array), and notes the problems that we can hope JWST will alleviate:

Detection rate of substructures: millimeter dust substructures were directly detected in only 50% of the targets in our sample. Our results suggest that the detection of substructures in disks around VLMS is limited by angular resolution and sensitivity, since the dust radial extent is very small and these disks are also very faint. Deep, high angular resolution observations over a non-brightness biased sample of VLMS should confirm the ubiquity of substructures in these disks.

This is going to be an exciting area of research. As the paper points out, for every ten stars that form in our galaxy, somewhere between two and five brown dwarfs also form, and we already know that low-mass M-dwarfs account for as much as 75 percent of the Milky Way’s stars. When massive objects form around or near brown dwarfs, we are challenged to adjust our models of interactions within the disk and re-consider models of gravitational collapse. Interesting brown dwarf issues await JWST if we can just get it into operation.

The Scholz paper cited above is “Size and structures of disks around very low mass stars in the Taurus star-forming region,” Astronomy & Astrophysics Vol. 645, A139 (January 2021). Abstract.